With its inch-perfect frame, OEM-style bodywork, and period-correct graphics, you’d be forgiven for mistaking this Yamaha for a forgotten 90s factory prototype. But what it really is, is a completely bespoke machine with a Yamaha XS400 engine, a whole lot of innovative engineering, and a patented front suspension system. Oh, and it was built by a hobbyist in a 13-by-15-foot workshop in Slovakia.

“The main idea of the build was to make it look as little like a custom bike, and as much like a factory bike, as possible,” says the mad scientist behind the project, Roman Juriš. “In purely amateur conditions and with a limited budget, I couldn’t get it one hundred percent right.”

Roman’s humility is admirable but totally unnecessary. The work done on this Yamaha could fill volumes—and the cohesiveness of the end product is at a level that even professional builders strive for. Still, he’s honest about the fact that getting there was no easy task.

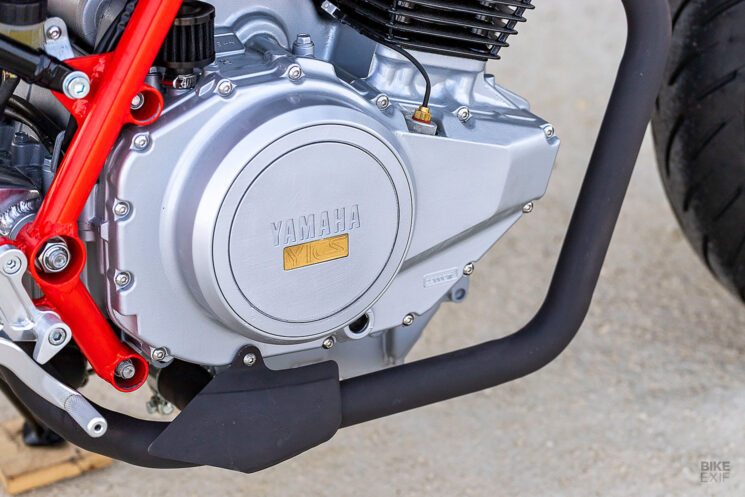

Roman started with a 1984 Yamaha XS400 non-runner, which he promptly stripped and started fabricating a new frame for. But he quickly fell into a rut, struggling to properly visualize the final design. “I tried to draw different versions, but it lacked the lightness and professional finish that I really wanted,” he tells us.

“While searching for inspiration, I found an e-mail address for the famous designer Oberdan Bezzi. To my great surprise, he started communicating with me, and finally sent me a single, but for me very rare, picture of a motorcycle with a design suitable for my frame.”

Once the design was in the bag, the real work began. Roman estimates that he spent 3,000 hours working on the project, spread over five years and two months. “Various craftsman friends did a lot for me,” he adds, “because my workshop is small and I simply do not have the necessary machinery and tools for everything related to the production of a motorcycle.”

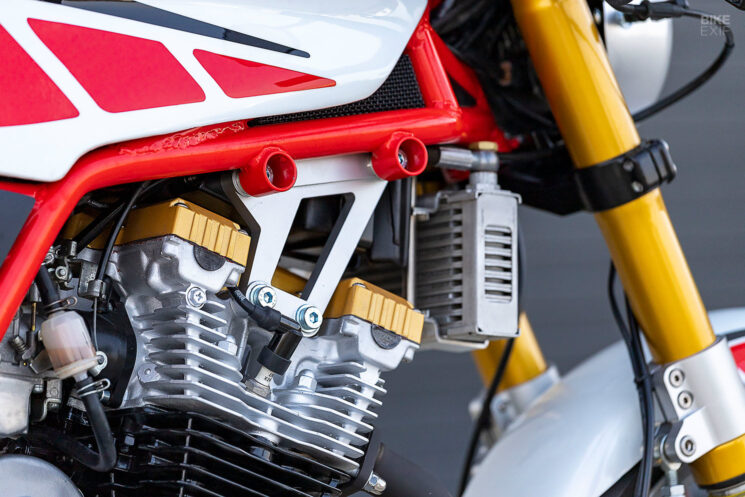

As for the bike itself, it’s hard to know where to begin. The XS400 motor hangs from a custom-made tubular frame via alloy mounting brackets. (The idea of suspending the engine from the chassis was central to Roman’s concept.)

The swingarm is off a Yamaha YZF-R125, which was technically Roman’s third choice. The first attempt involved fabricating a custom tubular swingarm, and the second used an Aprilia unit. In the end, the YZF-R125 part fit the bill—once Roman had shortened it by 80 mm.

To make the chassis even more unique, Roman then shifted the rear shock to one side instead of leaving it dead center; a detail inspired by the Ducati Scrambler. The 17” laced wheels are repurposed supermoto hoops. Roman sent the front wheel off to a workshop in Austria, who re-laced it to a Honda Transalp hub so that he could install twin brake discs.

But it’s the front end that’s truly intriguing. Roman calls it “progressive upside-down front suspension,” and currently holds the European patent (and a one-year worldwide patent) for it. “Obtaining a patent took almost two years—half a year of preparation, and a year and a half waiting for approval,” he tells us.

Without the ability to design the whole thing using software, Roman designed the front suspension the old-fashioned way. Technical drawings were followed by laser-cut steel components, that were put together to build a prototype. Once that was perfected, the prototype was sent to a third party to replicate in CNC-machined aluminum.

Roman is hush-hush on the nitty-gritty of how it all works, but he does cover the highlights. “It’s progressive, in the sense that for 120 mm of front wheel travel, for example, the fork only moves 60 mm. The axis of the front wheel is pushed forward, eliminating the shortening of the wheelbase, and the spring and braking forces are isolated, so the motorcycle doesn’t dive under braking.”

Since the setup behaves almost like a springer fork, Roman also had to build a parallelogram system for the front fender, so that it moves flawlessly with the front wheel. An LED headlight and small fly screen sit higher up, with a Koso dash mounted to the same handmade bracket that holds the screen. The cockpit also wears clip-ons, bar-end mirrors, and the original Yamaha switches.

For the bodywork, Roman once again turned to traditional methods. He used modeling clay to finalize the forms, then shaped everything out of fiberglass. The fuel tank is just a cover, hiding a metal reservoir underneath it.

A neat under-seat exhaust system finishes off the Yamaha’s ultra-skinny silhouette. Roman happened upon a deconstructed set of twin headers in the Netherlands, which he put together and matched to a pair of aftermarket mufflers. A custom-made tail tidy wraps around the twin cans to host the license plate and combination LED taillights.

As for the paint job, that came directly from Oberdan Bezzi’s design—with a few tiny changes. “The frame had to be red, like racing Yamahas from the 70s,” Roman explains, “and I wanted traditional Yamaha blocks, but in a minimalist style on a white background.”

“The style of the ‘Roadster’ inscription is a tribute to the Jawa 90 Roadster, which was produced in Slovakia from 1967 to 1976. It was a progressive bike that was, to its detriment, way ahead of its time.”

Roman also left all the aluminum parts raw rather than finishing everything in, as he puts it, “boring black.” He also spent countless hours polishing the swingarm, and settled on a simple cover for the seat, after a two-tone cover with contrast stitching proved to be too busy.

Roman concludes by admitting that it’s impossible to make the bike street legal in Slovakia—but that he added all the necessary roadworthy frou-frou anyway, to reinforce the production bike vibe he was going for.

We could pore over the details of Roman’s creation for hours, but there’s one major detail we haven’t mentioned—and that’s how damn good the refreshed XS400 mill looks in its new home.