There’s a long history of purpose-built automobiles that use motorcycle engines. Combine a strong enough motor with a light enough chassis, and the results can be very satisfactory. But what about sticking a car engine in a bike? That’s an entirely different ballgame.

Fans of vintage German engineering should recognize the power plant at the heart of this hand-built chopper. It’s powered by the air-cooled four-cylinder boxer from a VW Beetle—and, as you’d imagine, it took a little bit of ingenuity to put together.

It’s the work of Paul Clark—an English hobbyist that builds custom bikes for the love of it, rather than for commercial gain. A fan of older and rarer marques, he’s built up quite a collection of machines (and spare parts) over the years.

“I’ve built a Dnepr chop, and a J.A.P. rotavator-engined bike, as well as others,” he tells us. “These bikes are not shiny—far from it—and they are not something where someone will pull alongside and say ‘I’ve got one of those.’ They are unique to me, my style, and I love them—but it’s also nice when other people appreciate them too.”

Paul also likes to keep his projects low-cost, by using as many up-cycled and scratch-built parts as possible. This one kicked off with an eBay find; a £300 [about $379] VW Beetle engine begging for a home. “Using the engine as a base, sat on my workshop floor, I started to visualize the finished bike in my head,” he says.

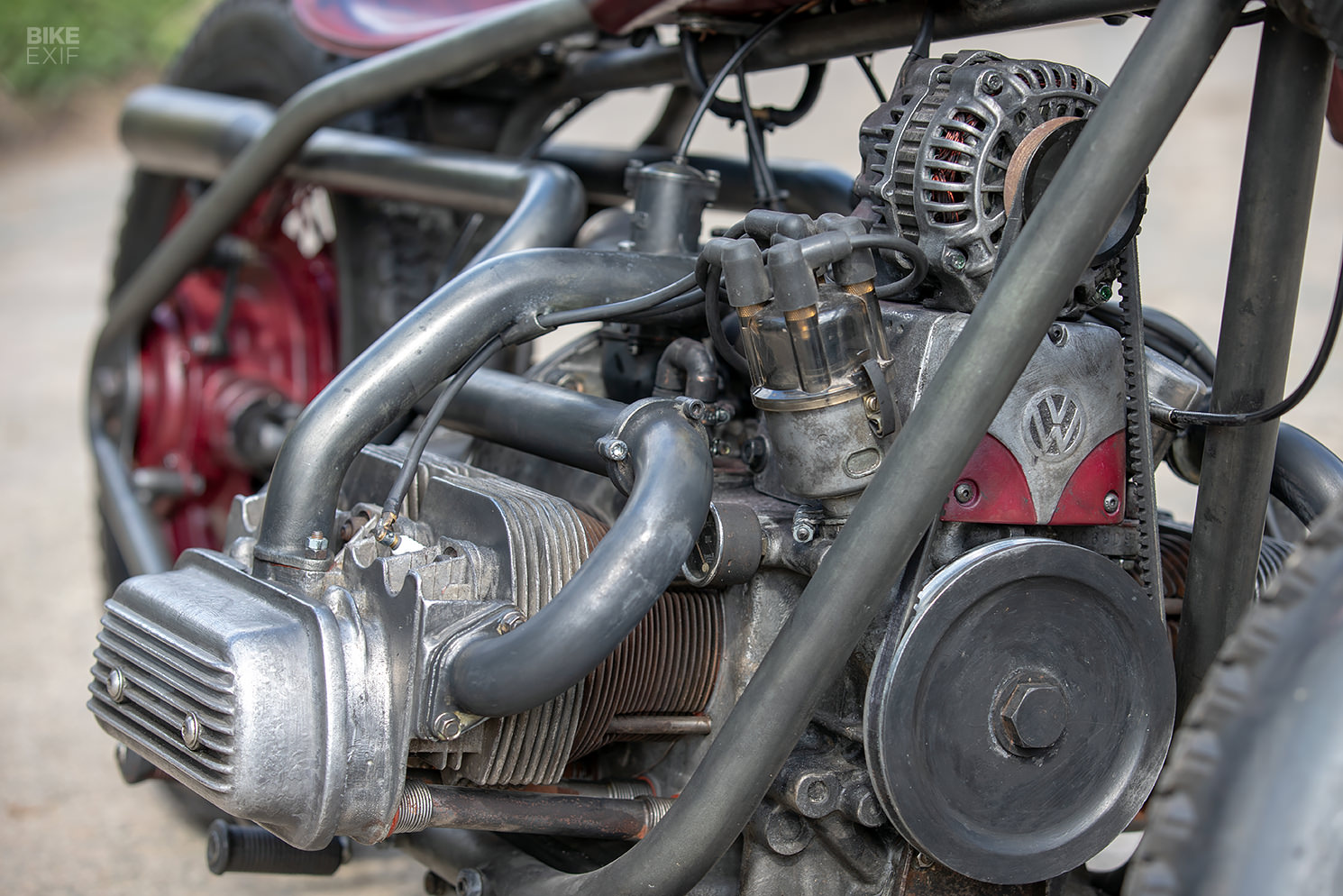

The first challenge was to attach a transmission to the motor. Paul mated a Dnepr MT 650 gearbox to the VW mill, via concentric flanges that were waterjet-cut from aluminum. A Dnepr clutch and flywheel were adapted to work, too, along with the alternator from a Kubota mini digger.

Wassel Evolution carbs inhale through an Amal velocity stack, attached via a custom manifold. The snaking pipes on either side of the engine seem messy at a glance, but if you trace them carefully you’ll be able to make out the line of Paul’s bespoke stainless steel, four-into-two exhaust system.

“Once they were fitted, they were dangerously close to the rider’s legs,” he adds. “I didn’t want exhaust wrap or heat shields, so I opted to buy some knee high boots to wear when riding; the things we do to keep the aesthetics as we want them!”

With the basics out of the way, Paul set up a makeshift wheel alignment jig using a steel beam. 16” rims were laced to a Dnepr front hub and a Honda Goldwing rear hub, shod with fresh rubber, and set in the jig, along with the engine and gearbox.

Starting with a partial 1983 Honda Goldwing frame, Paul mocked up the chassis with bits of spare tubing and broom handles (yes, broom handles). The final frame was welded up out of steel tubing, again procured from eBay, with the triples and forks from a Yamaha XJR1300 up front. The frame’s 50 mm stainless steel top tube also acts as an air reservoir, for a TC Bros ‘Air Ride’ system that sits under the slim chopper seat.

“I think that the seat always looks better as close to the tire as possible,” says Paul, “especially as there is no rear mudguard. It occurred to me early on that it would be great to have a seat that goes up and down—but I didn’t want springs, so I opted for an air bag. It looks great when the bike is parked up, and is really comfortable when riding.”

A small 12 V air compressor ‘charges’ the top frame rail to around 40 PSI, which is enough for the seat to go up and down about four times. Look closely, and you’ll spot a small air pressure gauge mounted just in front of the seat.

If the fuel tank looks familiar, it’s because it came off a Triumph Bonneville. Paul cut-and-shut it to sit wider, and adapted it to fit his frame. Just in front of it are custom-made handlebars, with Big Port Beston-style grips, a throttle, the brake and clutch levers, and little else.

Paul doesn’t like new and shiny bikes, so the frame was shot blasted and zinc plated, then wiped over with a firearm coating and stove polish. That gave it an aged cast appearance that would match the engine. First Choice Body Shop handled the red paint job, Central Wheel Components did Paul’s powder-coating, and Brimscombe Platers tackled all the polishing and plating jobs.

As a final touch, Whiteway Craft Foundry built a small battery box that doubles up as an alternator mount. The fact that it looks a little like an old VW bus is no accident.

With the project nearing the finish line, Paul pondered if his 132-pound frame would be able to kickstart (yes, he opted for a kickstarter) the chunky VW boxer. “Yes, it started—what a relief” he quips. “It’s actually quite easy to kick over.”

Almost ready for his first shakedown run, Paul then hit the biggest snag of the project. “I’m a bit of a hermit when building,” he explains, “but advice about strange technical details is always on hand from my oldest friend, Neil Baxter. He came over for a cup of tea one evening and casually said, ‘are you sure the rear wheel isn’t going to run backwards with the shaft on that side of the wheel?’”

“The propshaft was closely fitting with no room to change anything. We tried it, and, shock and horror, the wheel was running backwards! I was so dejected at this that I nearly scrapped the whole project—but with some encouraging words, it was a case of sorting out this unforeseen problem.”

In the end, Paul had to scrap the Goldwing rear wheel and bevel box, and replace them with a repurposed Dnepr final drive and hub. With a custom steel cover on the final drive, the whole arrangement only just fit into the frame—but the important thing is that it did fit. Two weeks later, the VW bike was ready for its shakedown.

“I got 20 feet, and it died,” says Paul. “A burnt-out coil seemed to be the problem. Two further coils later, it turned out that that the Lithium battery would not behave with the alternator, and replacing it with a small gel battery sorted the problem.”

Finally on the road, Paul’s happy to report that the bike pulls strong, topping out at around 60 mph. But since the Dnepr transmission has a four gears and one reverse gear, he might modify it to add a fifth gear.

“It’s not funny when you’ve spent a lot of hours building a bike, only to find that it has one forward gear and four reverse gears. Having to cut up a freshly built, laced and painted wheel is annoying in the extreme. That particular problem nearly did it for me—but I’m so glad it got sorted and the bike got finished.”

“The bike has its own logo, which is a reverse VW; the W on top with the V underneath, as a reminder to check such things much earlier in the build next time. It also goes by the name of ‘Bootsy,’ a reminder to put my new very high boots on unless I want to set fire to my trousers.”

Images by, and with thanks to, Del Hickey