In today’s digitally saturated world, communication is seamless, relentless and overwhelming. But Vic Matthews is part of a generation that didn’t grow up on the internet—his digital footprint is no larger than a seldom-updated Facebook profile.

So I only found out about his painstakingly restored Norton 16H via a succinct text message from my father; “Vic has just rebuilt this Norton!” And the instant that message popped up, I knew that Vic had brewed up something killer.

I arrange to meet Vic in Gordon’s Bay, a harbor town about 35 miles from Cape Town, where he and his wife, Kathy, have lived for the past six years. Vic, who’s now retired, is the most unassuming guy you’ll meet. He rides the Norton into the beachfront parking lot wearing track pants, running shoes and bright green socks, later donning Kathy’s wooly mittens to keep his hands warm.

As we roll the bike into place, he is as humble about his own work as he is critical, apologizing for the lack of period-correct double pinstripes on the bike.

“It’s not finished yet,” he says. “No-one will notice,” I fire back. “Those that know, will,” he replies.

Vic might not have a reputation online, but those who know him, know the quality of his work. He and my pops go all the way back to 1989, when they worked together in Cullinan, a small mining town in the northern part of South Africa. Since I’ve known Vic, he’s had a garage full of classic motorcycles, scooters and automobiles… all in various stages of repair.

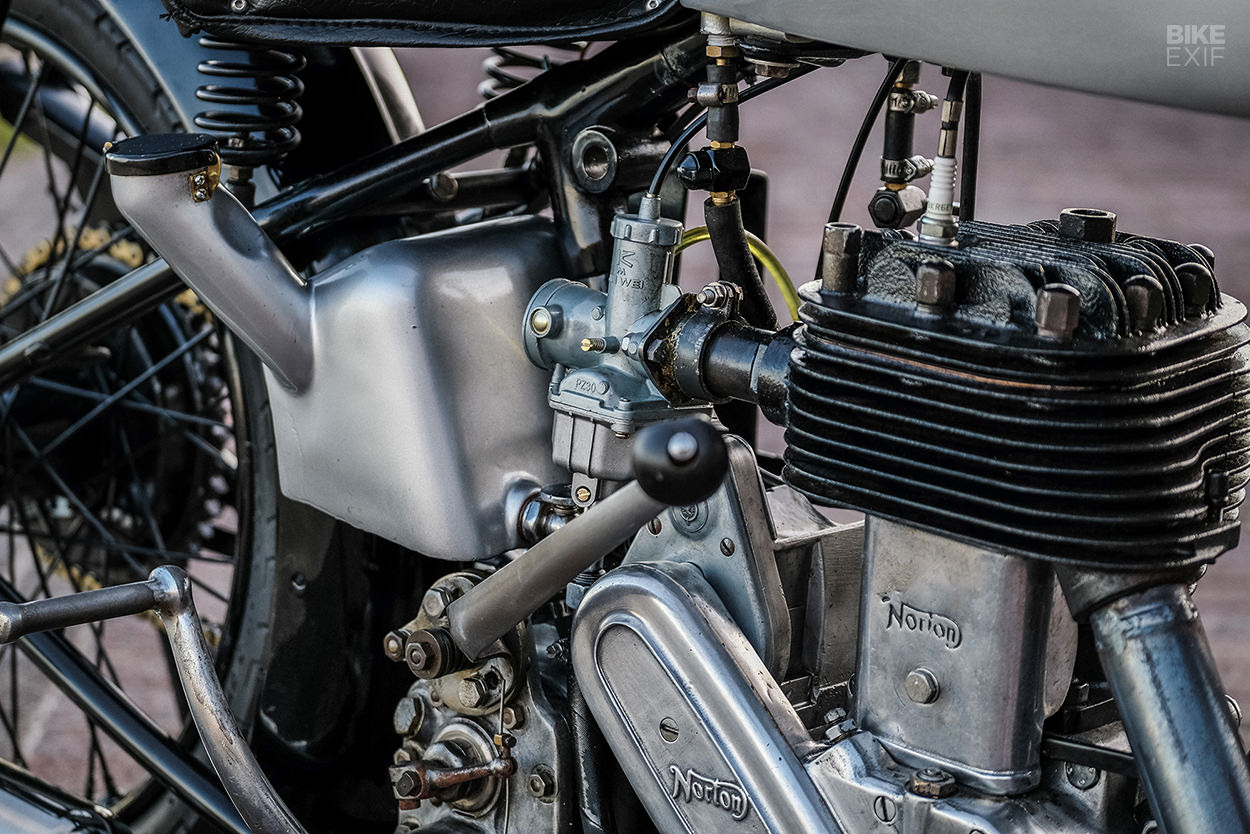

The Norton 16H was a 490 cc single produced from 1911 to 1954, used by the military and also sold to the general public. Vic quite literally had to bring this 1933 model back from the dead. “I bought the bike in Pretoria in November 1996,” he says “it was on a plot standing out in the open, and was badly rusted and in very poor condition.”

Vic stripped the bike down, had the parts repainted, and sent the oil and petrol tanks to be re-lined due to all the rust. He had the cylinder re-sleeved, and sourced a new piston all the way from Australia. But then he found, and started restoring, a 1972 Porsche 911—so the Norton was relegated to the corner, where it stayed for over two decades.

Vic’s interest in the 16H was rekindled earlier this year, when the global pandemic forced South Africa into a strict lockdown, leaving him stuck at home with nothing else to do but tinker. But he had another reason to restore it: he discovered that it was a 1933 model, having originally thought it was from 1938.

And that meant it was old enough to enter into a vintage rally that Vic had been eyeing.

The bike was missing a number of parts, but luckily Vic’s amassed a multitude of tools and machines over the years, and can handle most tasks himself. Bits like the foot brake, hand brake lever, front shock tensioner, oil cap, fender mounts, and a bunch of specialized nuts and bolts, all had to be replaced. “Fortunately I have a lathe, which was a big help,” he says.

Those parts that could be saved were cleaned, refreshed or restored. Vic had to rebuild the 16H’s girder front-end from the ground up, and he machined new spindle bolts for it, because the originals were beyond repair. The seat was treated to new springs and a new cover, and a full set of engine, wheel and steering head bearings were sourced from a local supplier.

Vic also machined down the big end crank pin, which was badly pitted, and installed new rollers. “I assembled and lined up the crank lobes myself,” says Vic, “which is quit a tricky job. Interestingly, no torques are given in the workshop manual to tighten the crank pin nuts—they just suggest you use a substantial spanner with a three foot long pipe to tighten them.”

Vic says that the biggest challenge was working out the valve timing. “On all the previous engines I have worked on, setting the valve timing is simple, as the gears are pop marked and all you need to do is line up the pop marks to achieve the correct valve timing. With this engine the gears are not marked, and also I was unable to find a workshop manual to show me how to do it.”

“Finally a guy on Facebook from the UK emailed me a workshop manual. The timing is set using a degree wheel—in other words, how many degrees before and after top dead center the valves must open or close.”

Vic rewired the bike too, but needed help overhauling the magneto. So he sent it to an 81-year-old gentleman on South Africa’s East coast. “This is a very specialized job,” he explains, “as the armature needs 1.6 km of wire wound onto it, and the magnets inside it need to be re-magnetized. He does a brilliant job. If he was not around I would have had to send it to the UK, which would have been very costly—and taken a very long time. Very few people know how to repair them.”

Vic has a few more things to tidy up on the Norton; the stripes for one, and a few parts that he wants to get chromed. But he’s not exactly sure when he’ll get to that. There’s a 1946 MG T-type that he needs to finish first, and a Norton Dominator is vying for his attention too.

For now, he seems all to content to just ride his enviable 16H. After a couple of failed kicks, some mumbling and a bump start, the Norton burbles out of the parking lot, and up the winding coastal road out of Gordon’s Bay. Kathy follows close behind, just in case Vic breaks down… or runs out of gas.

Photography by Wes Reyneke | Article adapted from issue 41 of Iron & Air magazine. Subscribe.