Our resident expert mechanic Matt McLeod reveals how he plans a custom motorcycle build.

I’m not sure about you, but I hate wasting time and money. So I’ve learnt that planning is one way to minimize the waste, and good project management will help you to stay on track with your custom motorcycle build.

We’ve already covered the books you need, the skills you need, and how to buy a donor bike. Now it’s time to plan and execute your build. There are plenty of ways to do it, and this is one example. Take this “template” and modify it to suit your situation.

I have a few other thoughts that might be best said at the start. Firstly, you might find it helpful to set a deadline for your build. Make it something significant, like a ride or a show that you want to attend. Nothing will focus you like a deadline.

Secondly, plans are just that: plans. They always change. They are never right. They are not set in stone. They are just a tool. As the situation changes with your build, the plan may also have to change.

Thirdly, you can compress the time frame to build your bike if you apply more resources. Let’s say you were building a house. If you doubled the number of construction workers on the job, you would be able to reduce the time taken to complete the house. Your custom bike is no different.

However, most of us work on our custom bike projects alone. Adding resources to speed up the build might mean “outsourcing” some of the work. Perhaps the engine needs rebuilding and you don’t want to attempt this step yourself. Or maybe you want a metal flake paint scheme that you can’t do in your own shop.

If you outsourced these jobs to a specialist, you could be working on other tasks in parallel. You could convince three friends to pull an all-nighter with you. These options would speed up the time frame but possibly increase other costs.

Working through a project is all about cost, time and quality. If you add “cost,” you might reduce “time” and increase “quality.” You can adjust the balance to suit.

Concept and the overall style

What style of bike are you building? This is probably the easy question: you probably have a collection of photos on your phone, or in an online album. There should be elements of the bike you want already in your head.

If you happen to be artistic, or have a career as a designer, then get sketching! Building out your bike on paper (or on the screen) is part of the planning process. This virtual construction will help guide your decisions during the build.

If, like me, you are more skilled with a hammer than a 2B pencil, there are other options. I generally prefer to find a drawing or photo of the frame of my project bike, and then sketch over it in a drawing app.

I use a really cheap Wacom One tablet with my Mac. I can add a tank, seat, tail section and wheels—even if they are just block shapes on the profile shot of the frame. This will help to confirm the proportions and lines of the project before cutting steel.

When you’ve got the shapes right, stick this picture on the wall above your build table. It will probably influence your choice of donor motorcycle, if you haven’t already decided what to buy.

Purchase the project bike

A couple of weeks ago, we covered what to look for when buying a bike. Download the checklist from my site to take along to the inspection. If you’re about to buy, let’s also recap two key points from the skills article:

1. Older bikes are generally less complicated and easier to work on—both mechanically and electrically. If you bought a current model bike, you’d have to consider all the “electrickery” that is needed to run the engine management system. Not to mention the ABS, traction control, wheelie control, electronic suspension and so on.

2. More common older bikes have more information and more parts available. If you want to build a Honda or Triumph cafe racer, or a Harley-Davidson chopper, these platforms have plenty of reproduction, second hand, “will-fit” and custom parts available.

Purchase parts

If you are after specific secondhand parts, you might have to buy them whenever they become available. Otherwise, there are online and “bricks and mortar” stores that can supply every known part you might want.

Depending on the condition of your donor bike, you might choose to reuse some items. And, on the flip side, there are some parts I would suggest putting straight into the trash.

These are some parts I might throw away and replace with brand new:

- The wiring harness, Especially if it’s already been modified. Will likely lead to reliability problems in the future.

- Roller bearings (such as wheel bearings, in the headstock, swingarm and so on). You don’t know what condition they’re in, so spend a few dollars and buy some more peace of mind.

- Filters (oil, air, fuel). Again, you have no idea what condition they’re in, or whether they are actually providing any protection to your engine.

- Rubber parts (cable and hose boots, grips, footpeg rubber, possibly tires). Age and sunlight are the enemy of rubber compounds. Some of these parts are likely to be recently replaced anyway, but inspect them all.

Once you start mocking-up your project bike, the parts shopping list should become more obvious. I like to keep new parts in their protective packaging for as long as possible—even until the final assembly. This minimises handling damage during the build process.

Teardown and sorting

Teardown can start immediately after buying the donor bike. But there are a few precautionary points to make.

If your project stretches out over many months, or even years, I bet you won’t remember how and where all the parts fit. Especially when you have a box of different bolts off the bike. So you need a system to catalog your parts and disassembly process.

A factory service manual and a parts manual are very helpful references to have. These will always be useful during the time you own the bike. Buy your manuals, new or used, on Amazon or eBay as soon as you have your bike.

The trusty camera in your phone is another very useful tool. Take LOTS of photos. Before you remove a part, take a photo of it in its location, then take another when it is removed.

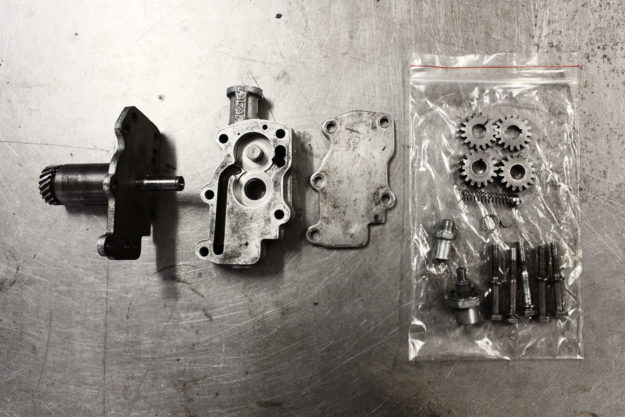

Ziploc® bags are a great help. Take the parts off the bike (with their mounting bolts or screws), take the photos, drop the parts into a bag, and write a description on the bag with a marker. If the mounting bolts are not identical, arrange them on your bench around the part and take a photo. This will help get it assembled correctly, months down the track.

Sorting, for me, means separating those parts that are reusable from those you will discard. This can be happening during the teardown. Some parts might be obviously junked; make a note of them, and add them to the shopping list. If you aren’t sure, just save it, and make a decision after cleaning and mocking up.

Cleaning

I’ve worked on a bunch of bikes, and those that are stripped, cleaned and repainted look amazing. Most of this work you can do at home.

You have to remove years of accumulated dirt, oil and grease. The resources you have available in your home shop will dictate how you go about the cleaning.

You need lots of rags. Hopefully you’re stockpiling old t-shirts that can be cut up and reused. Of course you can buy shop rags, but this is another cost you can avoid with some planning.

It’s possible to purchase aerosol cans of degreasing fluid, carburettor cleaner or brake cleaner to loosen the deposits on your bike. However, I think this could be the more expensive option.

A parts washing tub is really useful. A cheap parts washing machine with a small pump that circulates cleaning fluid to a stiff brush is part of my shop. You can substitute any large container that will hold the large parts on your bike. The pump is a luxury; nice but not essential.

You need to choose a cleaning fluid that you can purchase in quantity (say 5 gallons/20 litres) at a reasonable price. One option is concentrated degreasing fluid which can be mixed with water. I’ve had limited success with this approach. After a few months I had a nasty sludge in my parts washing machine.

So at the moment I use kerosene in my parts washer. This is not really cheap, but it is very effective. Gasoline is another cleaning fluid which works very well and is very cheap, but it’s also EXTREMELY hazardous, considering the other activities you might be doing at the same time. It’s obviously a very bad idea to leave a container of gasoline open in your shop.

My parts washer has a cover which keeps fluid in, and contaminants out. I also keep sparks from my angle grinder to a separate part of my shop. If you were cleaning small parts in a couple of cups of gasoline in the bottom of a bucket, you might be relatively safe. Just don’t, under any circumstances, put the dirty contaminated gasoline into ANY engine.

For extra safety, you probably want to get some chemical resistant gloves, and eye protection for splashes. And make sure you comply with any local regulations regarding use, storage and disposal of chemicals such as these.

Apart from a container and cleaning solvent, use plastic or metal scrapers to remove built up grease, and stiff bristle brushes for working fluid into oil and dirt. Once you’ve got all the contamination off, use rags to remove any residue, and dry off the parts. A final wipe with acetone, or a wax and grease remover, will really finish them off. Don’t forget to catalog them after cleaning.

I want the parts to be clean enough to keep my hands clean while I’m mocking up the build. I hate transferring oil and dirt from a partially cleaned part onto properly cleaned parts. It means you end up cleaning some parts twice!

If you have parts that are missing paint and are bare metal, you might see surface rust after a while. I don’t normally worry about this: I’ll clean it off just prior to painting. You could coat the parts in a protective oil, but I think this just adds more cleaning and extra work later.

Frame modification

Let’s say you are building a ‘bratstyle’ bike or a cafe racer. More than likely you’ll want to add a hoop to the rear frame. I have a couple of detailed videos showing this on a Yamaha SR400 (Part 1 and Part 2).

I much prefer to do this while the frame is completely bare and able to be positioned in any orientation. This avoids welding upside down under the frame, which means the weld quality should be better, and easier to clean up if needed. (If you are hardtailing a frame to build a chopper, the same process would apply.)

To decide where to cut the frame, it might be necessary to partially mock it up with the engine, suspension and wheels. Remember, “measure twice and cut once”!

All jokes aside, modifying a frame is serious business. If you do this wrong, you will compromise the structural integrity of your bike, putting yourself and other road users at risk. Certainly in my home state, the local constabulary take a dim view of frame modifications unless they see a certificate from a consulting engineer.

If you aren’t sure how to proceed, seek some advice from a local motorcycle shop or an automotive engineering professional—someone who can look after your safety and your wallet. There are many builders featured on Bike EXIF in cities all over the world; find one to help you progress your build, without taking shortcuts on safety.

Test fit/mock up

At some point you’ll be ready to assemble the clean parts you have prepared, plus any new parts you’ve bought. The idea is to build your bike almost completely before final painting.

Why? Because you’ll know that everything fits as expected. If you’ve forgotten some parts, you can go buy them. And you might find unnecessary parts that you can remove—such as frame tabs and brackets. You might assemble (and disassemble) the bike twice, five times, or even ten times before you are happy.

If you’ve painted the bike before this point, you’ll invariably damage your paint finish. This will mean more rework and wasted time.

A word of warning. I would advise always screwing or bolting parts up tight. In the industrial environments where I have worked, we marked bolt heads with a paint pen to show they had been torqued properly. If you have to move the bike, or choose to ride it before the final painting, you want to be confident everything is done up tight.

Wiring

I prefer to do the wiring after (or parallel to) the mock up. At this point, I’ve likely decided on and installed the lighting and other electrical accessories I need. I prefer to install, make or modify harnesses to the exact length needed. This reduces any joints in the harness which could be a future cause of electrical faults.

Depending on the model of bike and the modifications you have done, you might want to install a reproduction harness. If the modifications are extensive, making or buying a custom harness might be quicker and easier than modifying a new one designed for a stock bike.

Wiring need not be “scary.” With some learning and new skills, there’s no reason you can’t sort the wiring on an older bike yourself. Skill up with this series of videos in my electrical basics playlist.

The Final Teardown

Once you’ve got all the parts together on the bike, and the wiring is finished, you could theoretically ride the motorcycle. If you can’t wait any longer, then make sure all the bolts are tight and get out there!

This isn’t a terrible idea, except for chain lubricant flicking all over the rear of your bike. If you get all the fluids circulating, you might find a minor oil leak, for example. It would be preferable to find and fix that before it spoils your new paint work.

The final teardown also means separating out parts that need painting or more finishing. If you’re sending out your parts for painting, I would suggest packing them into boxes with bubble wrap or something similar. Your painter is more likely to repack the painted goods into the same packaging when they are finished. Then you’ll get them home in pristine condition.

Prep, Paint, Powdercoat, Polish

You can complete a lot of your preparation and painting in your shop. Will a professional painter get a better result? Yes, of course. But it’s definitely possible to achieve very acceptable results on your own.

If you are sending parts out for paint or powdercoating, make sure you discuss the preparation with your supplier. They might give you some instructions for completing some preparation yourself, which may save you some money.

If you are interested in doing some paint yourself, you can get an acceptable finish with aerosol cans. I normally paint frames in my own shop. I do use a compressor and spray gun, but the epoxy paint I use is also available in aerosol spray packs. I use these same aerosol cans of epoxy paint on small parts when I can’t justify setting up the spray gun (and then having to clean it).

Regardless of the paint used, the following are the typical steps you might follow:

Choose a paint system: head to your local paint supplier and ask for advice. When I say “system,” I’m referring to a set of products that work together to achieve your desired finish. This might be a specific primer, filler, base coat, and top coat of paint. Generally I prefer to purchase the “system” from the same brand. I can safely assume they’ve been tested together by the manufacturer and should provide good results.

Cleaning/Stripping: if you haven’t already cleaned the part thoroughly, you’ll have to do it now. The main reason I want the part clean is so I can assess the state of the existing paint. Theoretically you can paint over an existing coat, however I’ve learnt I can get a better finish by completely stripping the paint.

You can use a chemical stripper for this step, so follow the instructions on the product you purchase. But I believe I get a better result in less time if I use mechanical stripping. (You can see an example of me using angle grinder accessories to strip paint in this video.) If you don’t strip all the paint, you’ll need to fill any paint chips and sand them smooth if you are planning on a high quality finish. I can skip this step by stripping back to bare metal.

Masking: paint doesn’t need to go everywhere. You can use simple painter’s masking tape for protecting areas that don’t need paint, such as bearing surfaces, or screw and bolt threads.

Priming: follow the instructions on the product you have selected. Primer is needed to provide the link between the bare metal and the top coat of paint. If you have a surface that needs smoothing out, then you might use a number of coats of primer-filler which can be sanded smooth.

Paint: again, follow the instructions on the product packaging. With some care you can achieve a great finish. Here’s an example of me painting a motorcycle engine.

Powdercoat: I haven’t done much powdercoating. The main reason is I can’t repair a powdercoated surface with paint—without it being obvious. I personally prefer to paint in my shop. However, don’t let this discourage you. Ask around your local area for a powdercoater who provides a good service to motorcyclists.

Polishing: If you have parts to be polished, you might be surprised what you can achieve at home. In a nutshell, polishing is simply smoothing a surface with progressively finer grades of abrasives until the reflected light doesn’t show any surface imperfections. I’ve described my system for bringing metal surfaces to a mirror finish in this video.

Re-assembly

By now, you’re probably very skilled at assembling your bike…again. This is now the home straight. Get it together and get it finished!

Check that all the screws and bolts are tight. Fill the fork oil, fuel, engine oil, brake fluid, and coolant. Check the drive chain tension. Inflate the tyres to the manufacturer’s specifications. Check the engine tune, or have your mechanic finish it for you.

Make sure all the rider’s controls work properly. Check the throttle returns to the closed position when released. Ensure the clutch disengages the transmission completely.

Check that the brakes work before you start riding, and take that first test ride carefully. This is a brand new—and modified—bike, and you have no idea how it will handle yet.

Finally, don’t forget to find a photographer who can get those killer shots, and get your submission into Bike EXIF!

Tools for project management: my workflow

As a dedicated Google Apps user, I tend to keep all my project files in my Google Drive. This makes it easy to access them from my phone when I am shopping for parts.

I back up all my photos from my phone (including screen captures) to Google Photo albums. I use albums to sort photos depending on the project. I can also share specific albums to collaborate on projects.

Google Sheets are my favourite tool. I tend to plan and organise my builds (and everything else) with a Google Sheet. Here is a parts sourcing sheet for one of my projects. You can make a copy of it, and edit it to suit your build.

More recently, I have been experimenting with Asana. This is promoted as a project management app, but I think that might be optimistic. I would call it a “comprehensive task manager.” It does have better ways of displaying tasks than a list in a Google Sheet, but it is not a full blown project management application. Asana is free for single users (at the time of writing), so there’s nothing to stop you evaluating its features.

I hope you’ve picked up some tips to help plan your next build. What have I missed? What steps work better for you? Let us know in the comments below!

Bike build images are from the design and construction process of the PRAËM x BMW Motorrad S 1000 RR.