Motorcycle historian Paul d’Orléans takes a deep dive for Iron & Air into the uneasy but essentially productive relationship between the modern-day custom scene and design teams at the major manufacturers.

In the ancient days of the 1990s, custom motorcycles were incredibly popular, but their baroque excess made them irrelevant to the motorcycle industry. The death of the fat tire custom in 2009 made barely a ripple in the OEM world, but that was the first time, really, that customs were not leading motorcycle design by the nose, and folks forgot the unacknowledged back-and-forth between tinkerers making cool bikes—and the stodgy industry taking notes.

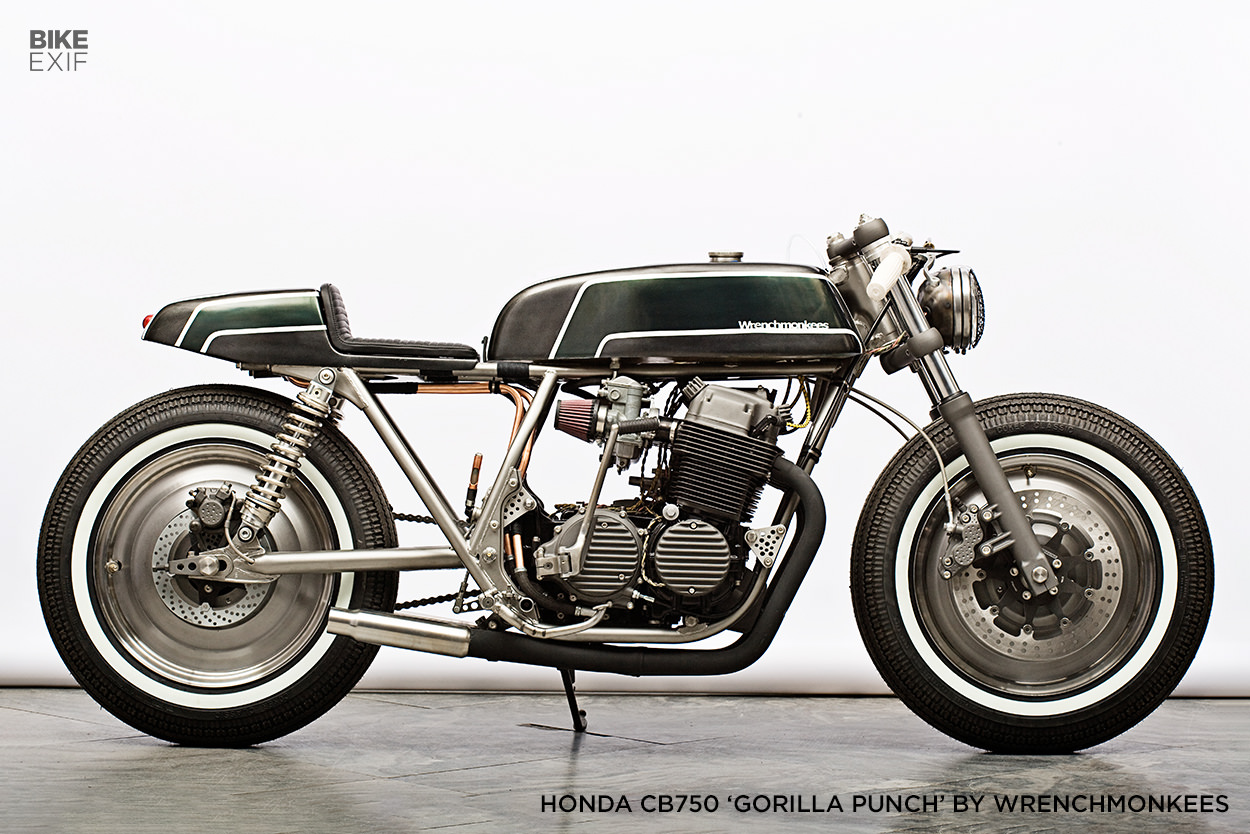

Going backwards in time, trackers, choppers, café racers, bob-jobs, Promenade Percys, and cut-downs had all impacted factory designs, but nobody talked about it until Bike EXIF became a monster. The site’s 2008 launch perfectly coincided with a mounting wave of excitement around a new custom motorcycle scene, and Chris Hunter caught the tiger by the tail. And without intending it, Bike EXIF and the neo-custom scene pulled the motorcycle industry out of its worst doldrums since 1957.

In short, customs saved the (motorcycle) world.

In a 2011 New York Times editorial, “Are Motorcycles Over?” writer Frederick Seidel asked if modern motorcycles are “kind of passé” and recognized that new bikes were no longer sexy or a necessary accessory for cool kids, who preferred their iPhones. OEM bikes had become heavy and complicated and tall, alienating the very folks the industry needed to survive: young people. As a result, the average age of a new rider in the USA went from 30 to 47 between 1990 and 2014, and the financial crisis of 2008 saw motorcycle sales worldwide drop by half.

But a whole new scene was building—out of the spotlight at first—stimulated by the very toxins that were killing the OEM industry: a poor economy, boring bikes, and the iPhone.

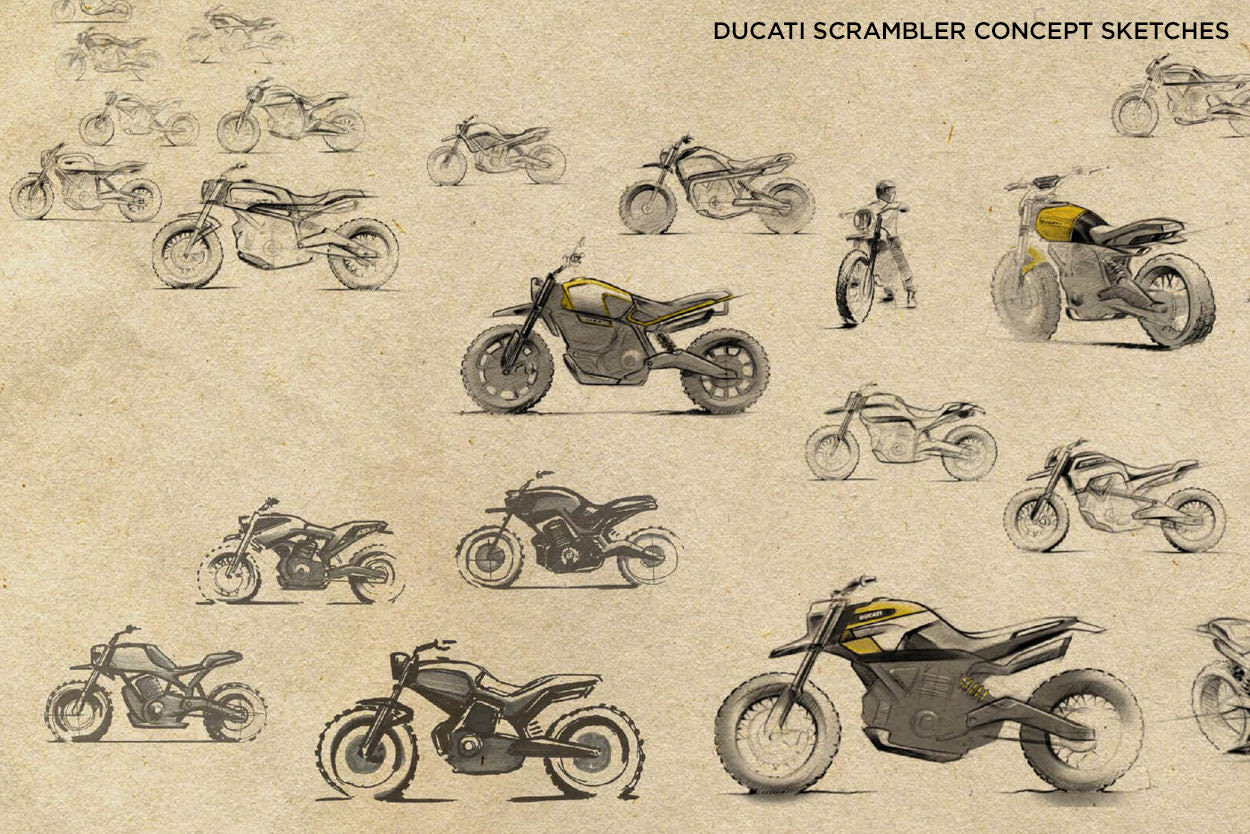

Enter the ‘CB’ custom, a shorthand for inexpensive donor bikes that could be made cool with not much effort—or a lot of effort, if you were determined and had skills. Let’s be frank: the average CB custom with a pipe wrap and Firestones did not change the motorcycle industry, but the energy that made them popular did. Young people vote with their feet, and blurring one’s eyes on the broad trends of 2009 revealed what riders really wanted: scramblers, café racers, street trackers, bobbers.

The motorcycle industry had once offered most of these styles as OEM models, like the Honda CL72, BSA Gold Star, and Triumph Hurricane, and bobbers had been around since the 1920s. The motorcycle scene had thrived in the 1970s with independent shops supplying all these styles, from Trackmaster and Rickman to a hundred custom parts suppliers in the pages of Easyriders. What happened 20 years later that nearly killed the OEM industry? Complacency, close-mindedness, and a business culture driven by anxiety.

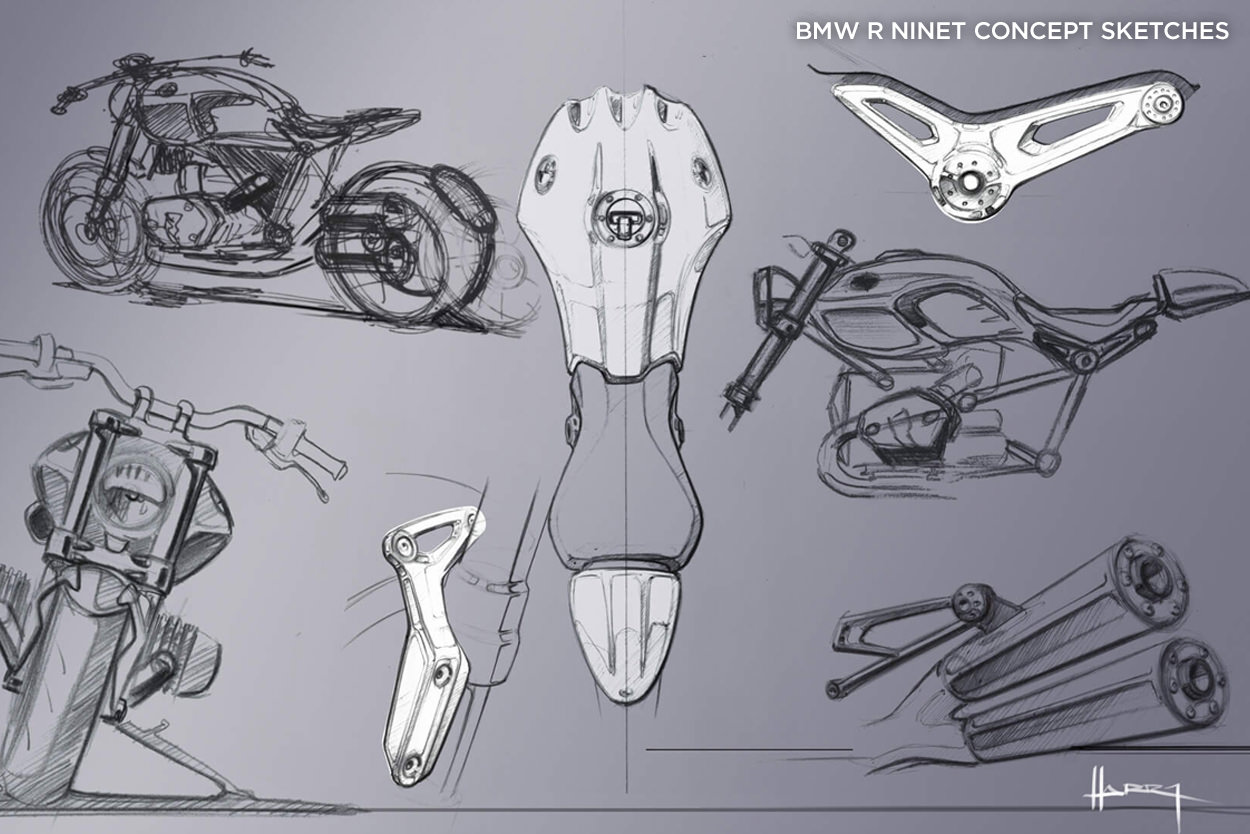

How did Bike EXIF, as the most popular and visible expression of a global custom scene, directly impact the industry? Ola Stenegärd, chief designer for Indian and formerly for BMW, says, “I was always building my own choppers, which were kind of an embarrassment to management in the early 2000s. [Fellow BMW designer] Roland Stocker and I saw that customs were getting big, with Bike EXIF the first bona fide expression of new customs.”

“We saw what was going on, and built the prototype R nineT in 2005. It took Hendrik von Kuenheim’s support, as head of BMW Motorrad, to show that bike at EICMA in 2008, and we had to fight for years with the Board to get it manufactured; it just didn’t fit their projections. Everything is about the numbers, there’s no room for a sales failure today, and getting the numbers to work in our favor was tough.”

“There were only two comparable bikes: the Triumph Bonneville and the Kawasaki W650, neither of which sold in the numbers we needed: 7,500 units just to break even. But the one statistic I could find in our favor was for tire sales! Strange, old-sized, 18- and 19-inch tire sales were going through the roof, and that was 100 percent because of the new custom scene. We were finally able to push the R nineT to market after eight years, and it sold out two years’ production in just a few months.”

More recently, Zero Motorcycles released an all-electric model, the FXE, which is the spitting image of an ultramodern supermoto that debuted at the One Moto Show in 2019, built by San Francisco-based shop Huge Moto. Zero commissioned Huge to do a custom build on a stock FXS without any intention of putting the resulting bike into production, but when Huge Moto’s creation debuted with such positive feedback, and with Zero’s aged platform needing an overhaul, the stars aligned.

Custom motorcycle builder Dave Mucci now works as lead designer at Zero Motorcycles, and when asked if he ever considered building a custom bike that could become a production motorcycle, he says, “It never once crossed my mind. Custom bikes came from people looking for something that didn’t exist in a showroom, so we just went out and built it, and what facilitated a lot of that is all the information you can get online now.”

“Before YouTube and blogs, people thought that since they didn’t know how to do something, they couldn’t do it. But now how-to videos are constantly thrown in front of you, and you get the knowledge you need to build something yourself that didn’t exist in the world before. Now, so many people did that, that it’s driving the industry to change the categorization of its models and go in different directions than it previously would’ve.”

Discussions with designers at other OEMs confirmed identical scenarios: the desire of design staff to experiment and follow trends created by young motorcyclists, stymied by a corporate culture of anxiety. But eventually, the evidence was overwhelming on all sides: the kids wanted cool bikes, and the factories needed kids to survive.

Bike EXIF, as the harbinger and representative of a new scene, very much changed the motorcycle industry, as acknowledged by its designers. The collaboration of OEM factories with small customizing shops like Blitz, Brat Style, and El Solitario only emphasizes the desperate need of factories for new ideas and new energy. And the bikes most clearly impacted by the neo-custom scene—the BMW R nineT, Ducati Scrambler, Triumph Scrambler, et al—tend to be the most popular in their lineups.

The game is far from over, though. We’re watching the electric custom scene grow, with the usual mix of spectacular and humdrum designs coming out of workshops around the globe.

Talented customizers are now recognized as design trendsetters by the OEM industry, and we’re seeing their immediate impact on the entirely new EV industry—not as late-hour saviors, but as the very creators of the future of motorcycling.

Put on your capes, customizers. It’s time to save the world again.

Illustration by Justin Page | Article originally featured in issue 45 of Iron & Air Magazine. See it online here, or subscribe here.