Walt Siegl builds dream machines. They’re analog fantasies on two wheels: limited edition European thoroughbreds packed with unobtanium components and clothed with impossibly beautiful bodywork. Bucket list material for the discerning petrolhead.

But Walt has just done a 180-degree spin, and turned his attention away from the bellowing Italian twins and triples that have made him famous. He’s formed a partnership with industrial designer Mike Mayberry to explore the potential of electric motorcycles.

Walt believes that electric bikes are the gateway drug to get younger folks onto two wheels. “I think that electric bikes have a strong future,” he says. “Young people embrace the romance and fun of traveling on two wheels. Newcomers don’t have the reference to combustion engines, so they won’t miss them.”

And for Walt, electric power distills the riding experience. “There is no sound other than the wind. It’s the next best thing to flying. I feel like I enjoy riding even more, because it happens in silence.”

Mike Mayberry is another fan of magnetic fields and electric currents. If his name sounds familiar, it’s probably because he’s the co-founder of Ronin Motorworks—and the man behind the striking Ronin 47 bikes.

All 47 of those Buell 1125-based machines have now been built, and the workshop and design studio have closed. So the time was right for Mike to hook up with Walt and explore new avenues in motorcycling.

“We have similar philosophies on what makes design approachable and appealing,” says Mike. “Design is not a styling exercise: it’s a journey in problem solving.”

He’s a man of eclectic tastes and few preconceptions. Like this writer, he has a Husqvarna Vitpilen in his garage—alongside a BMW R 1200 GS, a Cake KALK electric moto, and his most cherished possession of all, a Walt Siegl Leggero.

In total, Mike has four electric motorcycles that he rides regularly, “and maybe another eight or ten electric bicycles. They’re all different, and all a blast in their own way.”

Mike’s enthusiasm for electric power has rubbed off on Walt. And they share a design philosophy too. “Really good design is just as fresh and relevant 50 years after its creation as it was on day one,” says Mike. “Walt and I both feel strongly about this, and that’s a big part of why we are working together.”

It’s an exciting prospect, and to be honest, probably the kind of kickstart the electric motorcycle industry needs. Zero is the highest-profile manufacturer in the USA, but even so, its annual sales are a drop in the proverbial ocean. Harley probably sells more Street Glides alone in one month.

Why is this? Especially when electric car sales are going through the roof around the world? We’re betting it’s because most cars are utility purchases—a means to get from A to B. Whereas motorcycles are ‘enthusiast’ purchases, and most riders place more value on the traditional, visceral pleasures of speed and noise.

“I think all of us dyed-in-the-wool motorcycle riders should at least try an electric bike, to form an opinion,” says Walt. “I’m fully aware that electric-powered technology is not the final answer to our planet’s pollution problems, but I see it at least as a step in the right direction.”

Walt and Mike decided to amp up the sex appeal of electric power, and to our eyes, they’ve succeeded. ‘PACT’ is edgy—in all senses of the word—and doesn’t attempt to smother its drivetrain with trad ICE bike styling cues.

“Without disparaging other brands, I’ll just say there aren’t currently any bikes that speak to us, or make us want to own them,” says Mike. “This is a big deal to us…Walt and I both wanted that ‘connection’ with an electric motorcycle.”

We wondered if PACT was an acronym, but it’s not. It’s a little deeper than that. “It stands for friendship, agreement with all elements of the project, and a commitment to new, green technology,” says Walt. The bike shown here is the first production build; the prototype is in the Petersen Automotive Museum in LA.

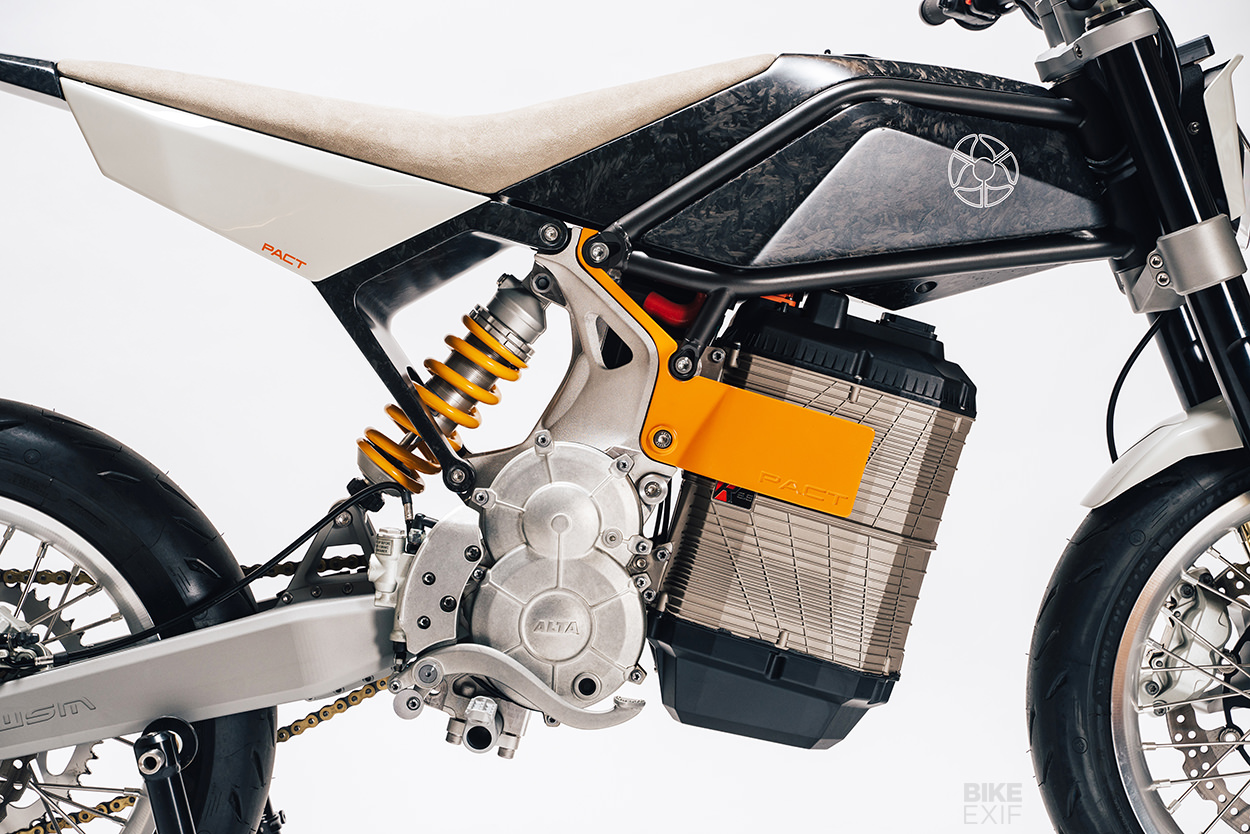

The core of the bike is the Alta Redshift drivetrain, which delivers a near-instant 50 horsepower. The liquid-cooled motor spins to 14,000 rpm, weighs a mere 15 pounds, and sucks juice from a 5.8 kWh li-ion battery that can recharge in three hours from a standard 120v socket.

“I cannot say enough good things about the Redshift components,” Walt enthuses. “The guys at Alta didn’t cut any corners anywhere, and attention to detail is apparent everywhere. That was the reason we picked the Redshift as the donor bike.”

Walt and Mike have designed a new frame to cradle this motor, using street bike geometries. (Walt’s righthand man, Aran Johnson, is an expert flat track racer and his help was invaluable here.) They built a jig before constructing the frame, and used 00.65 wall chromoly tubing. It’s a traditional approach, but the critical brackets use cutting edge techniques: they were first 3D printed, put in place to ensure correct alignment, and then CNC’d in steel.

When it came to the bodywork, Walt reached into his store of paper and cardboard, to understand dimensions and size better. “Dimensions in computer modeling can be misleading,” he notes.

The prototype bike was built with woven carbon fiber sheets, but Walt and Mike have used ‘forged’ carbon fiber for this machine. “I used this process few years back on the David Yurman MV,” Walt explains.

“The parts are made using compression molds, so tooling costs are significantly higher—but the result is even stronger than woven carbon fiber, and looks killer. As far as I know, WSM is the only motorcycle company that uses forged carbon on semi-production level.”

The subframe is also carbon fiber, and includes a storage compartment for things like the charger cable. “The weight of the subframe is three pounds,” Walt reveals. “The bodywork weighs five pounds. The whole machine comes in at 251 pounds [114 kg].”

That’s Honda CRF450R territory, and pretty impressive for a machine with a battery pack.

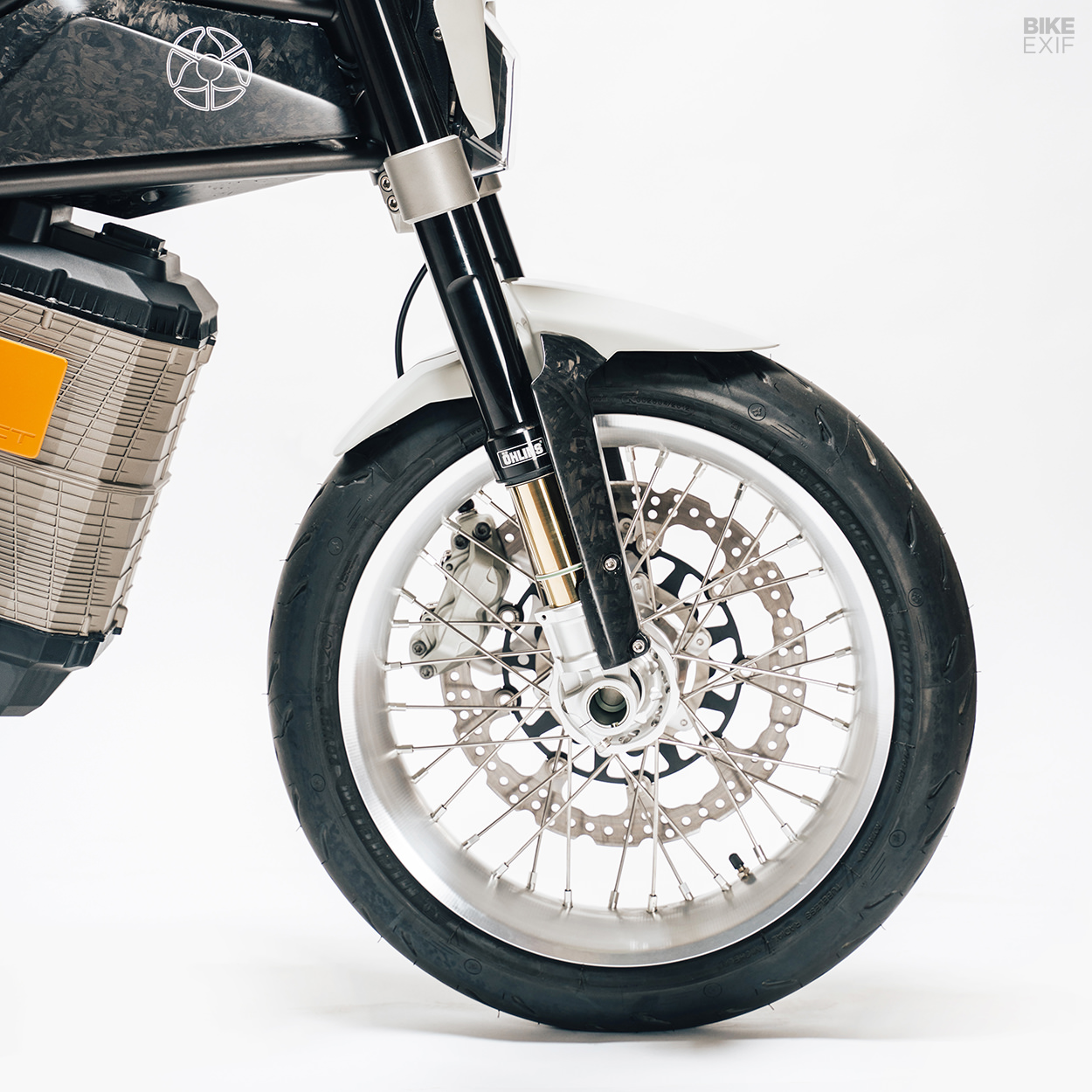

Mike designed a new swingarm that’s shorter than the Alta unit, and to accommodate the Alta’s weight reduction, Walt has fitted new springs in the forks. He’s also lowered and re-shimmed the rear shock, and machined up a new aluminum linkage. The triple trees are new, too.

Firestones simply wouldn’t cut it on PACT. “We wanted to run high performance tires and light wheels, so we developed our own rims,” says Walt. (As if it was as simple as welding up a battery box.) The new rims were modeled in 3D and then CNC machined.

Despite the multiple angles on this machine, it hangs together incredibly well. You just know that Walt and Mike sweated every millimeter of the build, and there’s no hint of committee decision-making compromise.

“There can be synergy if the combination is right,” says Mike. “We lucked out, I suppose. We happen to complement and challenge each other.”

Walt describes PACT as a ‘very personal’ project, geared towards his and Mike’s tastes. But the plan is now to build six more machines, available to order through WSM.

If that’s sparked your interest, drop Walt a line.

Walt Siegl | Facebook | Instagram | Images by Gregory George Moore

Adapted from an article written by Chris Hunter for Iron & Air issue #36.