The first feature on ‘How to Build a Café Racer’ struck a chord. Not everybody who read it agreed with the content, but when it comes to style, there are several different schools of taste.

I’m going to focus on the performance side of building a cafe racer. Or street tracker, scrambler, or any custom motorcycle, for that matter. Let’s start by picking the right bike up front to avoid expensive mistakes down the track.

1. Choose your weapon. The most affordable motorcycles to customize are the bikes that time and style forgot, and many are Japanese. That means the Honda CBs, in the 350, 360, 500, 550 and 750 capacities.

Yamaha has the XS series, in 360, 400 or 650 capacities. Forget the XS500 or TX500, unless you’ve got tons of time and money. Then there’s the SR400 and SR500, and even the Viragos are now getting lots of attention.

From Kawasaki, you can pick a Z of any size. But it was Suzuki that produced some of the best air-cooled inline fours, like the GS750/1000s—which is why Pops Yoshimura gave them so much love. And why you see hardly any for sale these days.

2. Know the issues. All these bikes will most likely have the same issues, because they were all manufactured at least 30 to 40 years ago. We’re talkin’ about the 70s, when bikes were gaining power with each new model year but the handling was lagging behind.

By 1972-73, almost every bike was sporting a disc brake up front. Intake noise was still audible, and most wheels had wire spokes. Shocks were mostly chrome spring holders, and low-hanging mufflers and centerstands caused lots of sparks (and crashes) when cornering at speed.

Lessons were learned and improvements were made. As the bikes were pushed to their performance limits at the racetrack, improvements gradually made their way into production models. These lessons, tricks, new parts and tuning secrets have since continued to gather, so we now have a huge pool of knowledge.

I should mention it’s always a good idea to choose a bike that has decent parts availability—plus a wide selection of aftermarket goodies. Putting a lot of effort into a bike that you can’t even buy a head gasket for is the start of a frustrating journey.

3. After your purchase. Let’s say you bought a 70s bike cheap, with the intent of building something really cool to dazzle your friends. Maybe you’ll ride it every day to work or school too.

After many nights in the garage, the bike runs decent and you’ve done all the things that everyone else does to make your bike look cool. But you’re starting to think, “Wow! This thing is like a slow, wobbly 40-year-old buckboard.”

When you go for a spirited ride in the hills with your friends, maybe the bike isn’t all that exciting or confidence inspiring. Or it’s just plain unsafe. Or maybe there are a couple of guys with bikes from the 80s or even the 90s disappearing over the horizon. You’re thinking, “It’s got to get better than this!”

Unfortunately, bikes have been improving at an exponential rate over the past thirty years. But you’re committed to riding your 70s bike, and want to be able to say you built it yourself. It’s time to improve it, while keeping a realistic view of how much you can improve it before you’ve depleted your resources.

4. Make a plan. You’re gonna need a few things. Starting with a direction and gathering knowledge is a must. What can you afford? What should you do? How do you find out, and whom can you ask?

If you search the web and look at pictures of 70s racing machines and hotted-up street bikes, you’ll find clues. The stance was usually changed, as were the tires. Aluminum rims replaced steel, and generic aftermarket shocks and fork kits were installed. You often saw braided stainless brake lines and a second front disc and caliper. Frames were heavily gusseted, and so were swingarms—or they were upgraded with aluminum items.

In the engine/performance department, you’ll need to dig a little deeper: Pictures will show only the external mods. You’ll notice air cleaners, bigger and better carbs and exhausts, and perhaps some sort of oil cooler. To get an insight into internal mods, you’ll need to read articles from old magazines that have hop-up tips pertaining to your bike. And then look for those parts at swapmeets or on eBay if they are no longer manufactured.

Another way to gather knowledge about the older models is to attend a vintage race or two. There are classes for all displacements and different eras. The rules are generally intended to keep the bikes period correct, but most of the parts needed are readily available.

5. Get to work. All bikes like Honda CBs, the Yamaha XS and SR series and Kawasaki Zs can be improved with a standard group of upgrades, beginning with the chassis. Inspecting the frame for cracks or damage is the first step.

Factor in tapered steering head bearings or, at the least, replace the worn out stockers with new OEM bearings and races.

Most of the older bikes came equipped with a plastic swing arm bushing. This should be replaced with a needle roller bearing kit in solid bronze or new-old-stock ones.

Another area of concern would be the swingarm pivot shaft and reducing the side-to-side play of the swingarm down to the factory minimum spec. Up and down movement should be without restriction, but side-to-side or axial play should be almost nonexistent.

6. Spend on suspension. It’s time to cut loose. Namely, new shocks and a fork kit. Getting shocks from Öhlins, Racetech, Works Performance, Hagon or Progressive Suspension can all be an improvement.

That said, it’s absolutely critical that the dampening and spring rates are matched as closely as possible to the weight of you and your bike, taking into consideration what type of riding you’ll be doing. Buying a name brand shock that’s mismatched, already used, or designed for a race bike may not yield any improvement whatsoever.

I know that Racetech and Works will build shocks to exactly fit your needs. Lengthening the rear shocks eye-to-eye can get you more cornering clearance and better turn-in for corners. But lowering the back end of the bike, as seen in many current custom builds, has the opposite effect.

The same goes for forks. Scoring a set of cool USD (upside-down) forks on eBay in no way guarantees good handling. But a fork spring and a dampening kit (or Racetech emulators) can yield great results with your stockers if they aren’t bent or rusted. You can even adapt better forks to fit, possibly from a different model of the same brand.

7. Add lightness. Another way to improve the stock chassis is to lighten the wheels and fit better brakes and tires. There may be a similar model to yours that has a lighter, smaller rear hub, or a smaller and lighter disc.

Look at lacing up an aluminum rim, perhaps wider, that allows you to use a better tire. Firestones or knobblies on your street bike are a loud, clear signal that handling in the corners is of no concern, and the other things I’ve mentioned to get the chassis to a higher level will be for nothing.

8. Tires. Every tire manufacturer makes rubber donuts in the 18” range that will give good grip and great transitions from vertical to leaned-over. A lot of the 70s-era bikes—almost all except those in the sub 450cc range—came with 19” front wheels. These combined a steel rim with a large diameter, and generally speaking, a much more ‘relaxed’ steering head angle. This increases the gyroscopic effect and leaves you with a bike reluctant to lean or steer into a corner.

9. Brakes. While we’re up front, how about braided stainless brake lines and new pads? Discs can be swapped out for a larger disc from another brand or model, or you could even swap the front hub for something that originally came with two discs.

Note: make sure you also pick up a brake master cylinder intended to push enough fluid for two calipers! Many older bikes had caliper lugs on both fork legs, but oddly no caliper was attached. When you visit the vintage races, you’ll observe that most bikes will have been converted to aluminum rims with an 18” wheel at the front and most likely a second disc.

Other factors are the steering head angle and triple clamp offset, which feed into the “trail” part of the overall package. That’s a discussion for another time, but it’s a huge factor in handling.

10. Get your timing right. Ok, so now your bike goes straight when you want it to. It doesn’t wobble and the new wheels and tires—being lighter—feel pretty darn good going into and through corners. Not to mention the dual discs slowing the bike down with much less effort.

But if only it had more power! Well, the solution isn’t as obvious you’d expect. At first, anyway. The guys who have been successful at competition over the years don’t just throw some trick component at the bike and go faster. They keep the stock engines or modified engines in top condition throughout the year.

They aren’t up all night playing World of Warcraft. They’re in the garage setting the timing over and over till it’s perfect. Or resurfacing the head and cylinder, so with a new gasket, it won’t leak—ever.

So start by making sure the engine has good compression on ALL cylinders. Check the points are in good condition, and the engine is timed correctly. The air cleaner(s) need to be clean, and the carbs jetted properly—since you tossed the airbox and installed the cool “pods.”

11. Rebuilding the engine. Most bikes from the 70s are tired, pooped out and thrashed. A paintjob won’t get it down the road any quicker. You may need to bite the bullet with an engine rebuild, and once again, the vintage races could be your best source. The Yamaha TT500s (with the same motor as the XT and SR500s) are probably the most popular bike in all flattrack races, week in and week out. With a 540cc kit, a Megacycle cam, a Sudco 36-38mm round slide carb kit and just about any pipe, you’ve entered another world of performance.

Same with an XS650 Yamaha. A 750cc kit, Megacycle cam and some 34mm carbs—and CB750s look out! That is, unless your CB owner got a hot cam, a 836cc big bore kit and some Keihin CRs while building his own cafe racer, and paid attention to his chassis set-up.

12. Learn from the hot rodders. The common thread on all these bikes is giving a crap about the chassis set-up, getting the motor at the least back up to “Blueprinted” stock and then using all the standard hot rodding techniques racers have used since the internal combustion engine was invented.

Bigger displacement, more cam, better ignition systems, bigger/better carbs and you can even install exhaust systems that yield more power and are still quiet. There are so many parts available for the older bikes that have evolved over the last thirty years; everything can just be purchased and installed with vendors providing detailed instructions and technical assistance.

Good luck with the project!

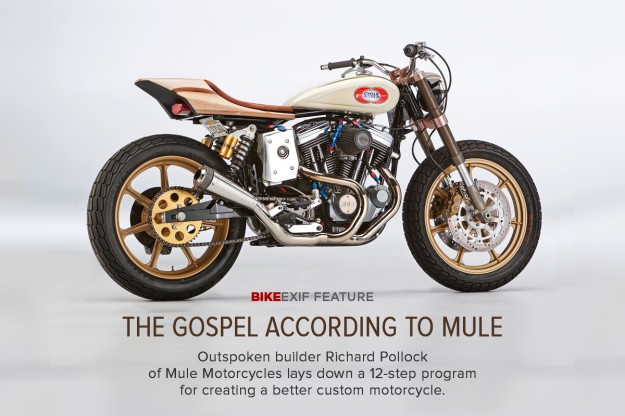

Check out our extensive coverage of Mule Motorcycles in the Bike EXIF archives.