Most of us know Mooneyes as the brand behind Japan’s most prestigious custom motorcycle and car show. But the company’s history can be traced back to 1950s America, when its founder, Dean Moon, started making a name for himself in the Southern Californian hot rod scene.

One of Moon’s most notable creations was the Mooneyes Streamliner. With an aesthetic somewhere between art deco and futuristic (for the 60s), the Streamliner was a land-speed racing car with aerodynamic bodywork and a bright yellow paint job. It was also the inspiration for this outlandish twin-engined Triumph drag bike, built by James Rogers in Gloucestershire, England.

James is far from a typical custom motorcycle builder. He damp-proofs basements for a living, building custom bikes after hours as a creative outlet out of a single-car garage, armed with little more than a grinder, welder, and heaps of imagination. “I have no engineering background,” James admits. “I just have a go.”

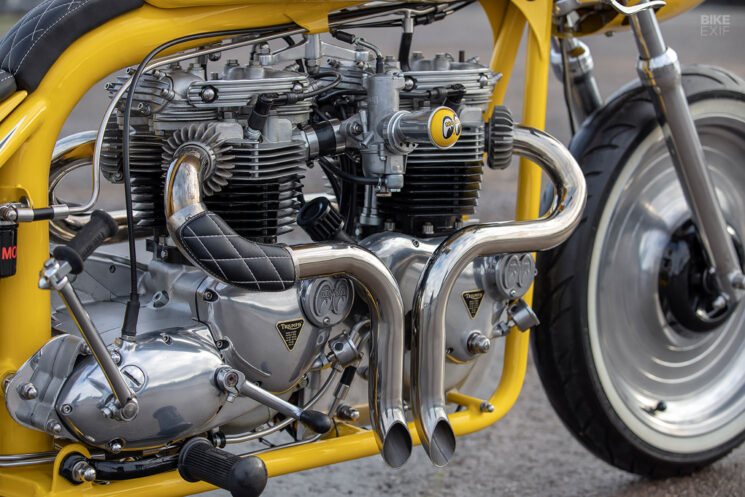

“This project started off with two damaged Triumph TR6 engine casings that were garage wall art. Then I was given an oil-in-frame T120R whose con-rod had a disagreement with the crank. I started looking at twin-engine drag bikes from the 60s, 70s, and 80s, to see how they linked the two engines together—this is when I noticed that no one had ever put a Triumph pre-unit and a Triumph unit motor together.”

“With this in mind, I wanted to build a road-legal twin-engine bike with a hot rod theme. That’s where the Mooneyes inspiration came in. I’m a big fan of Mooneyes and an even bigger fan of the Mooneyes Streamliner, which is what I based the bike on.”

James’ first job was to fabricate a new chassis around the oil-bearing section of the Triumph T120R’s frame. So he built a frame jig out of boxed steel sections from his local scrapyard, and then ordered tubing to use for the frame itself. “I called a guy I used before to bend tubing, and asked him if he could bend the tubes for me,” he recalls. “He said, ‘The key is next door to the unit, go and help yourself,’ which I did.”

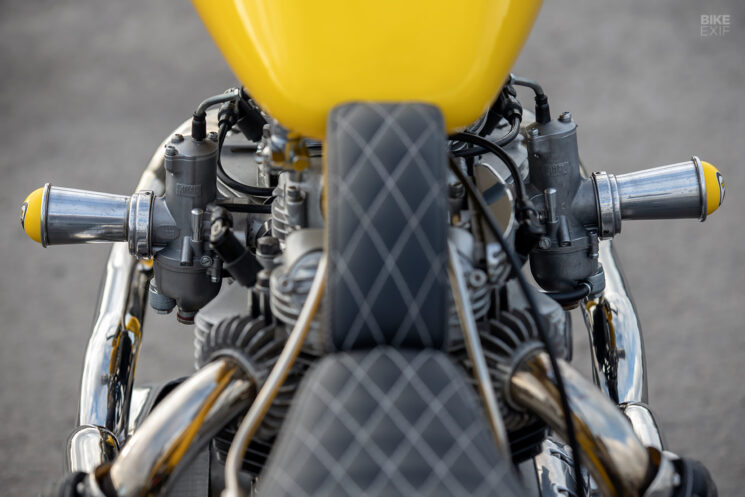

“I didn’t want the bike long like a traditional drag bike—I wanted to make it rideable for the street. So I looked on the web and found an alternator that was two-and-a-half inches in diameter, which meant I could set the handlebars three inches closer to me and move the engines back in the frame. With this in mind, I started to weld the frame up.”

The bespoke frame features a rigid tail with a set of 2001-spec Harley Sportster yokes and forks up front. It rolls on a set of restored Harley V-Rod wheels, equipped with stainless steel brake discs, modern Triumph calipers, and handmade braided brake lines.

James happened upon the wheels (and the bike’s bodywork) by chance while visiting the nearby Cheltenham Harley-Davidson showroom. “I got chatting to the guys about my project and what I was looking for, and they kindly took me to the back of the workshop,” he tells us. “It was like Aladdin’s cave—it had everything I needed, but with a slight problem…”

“Like the parts I started this bike with, everything was damaged. There was a dented Harley Road King petrol tank, a twisted and dented Harley Road King front mudguard, and water-damaged Harley V-Rod wheels. So I only paid scrap metal prices for them.”

Armed with the beat-up donor parts, plus a drag racing cone fairing that he convinced a business partner of a friend to sell to him, James began beating his two-wheeled Streamliner into shape. He cut and shut the Harley tank to match its width to the fairing, before knocking out the dents and fabricating a new tunnel and mounts. Then he restored the mangled Road King front fender, flipping around and modifying it heavily to turn it into a tailpiece.

Once all the bits were on the frame, James realized that he didn’t like the gap between the seat and the fuel tank. So he took a section of stainless steel exhaust tubing and used it as a base for a small tummy pad. “Now it looked right—and I had somewhere to rest my belly and not scratch the paintwork,” he adds.

When it came to building the engines, James had a mammoth task ahead of him. All he had at the start were the two damaged TR6 casings—one unit, and one pre-unit—and a pair of dual-inlet T120 heads. “I had no internals for these engines,” he says, “so I made a phone call to Miles at Autovalues Engineering, and chatted about what I wanted to achieve.”

“That’s when he said that he had just cleared out his late father’s garage, and found two sets of Morgo con-rods, still in their boxes. I had to have them—along with two sets of barrels and pistons, two pairs of tappet blocks, rotary oil pumps for a pre-unit and unit, stainless base nuts for the barrels, two remote oil filters, and a load of running-in oil. I thought, ‘What have I started?’”

A trip to Ebay (which James refers to as “The Bay of Dreams”) produced matching lightweight late-60s cranks, E3134 cams, type-R tappets, push rods, and cam gears. James wanted the arrangement to look symmetrical, so he reversed the rear engine’s head—that way, each side of the bike would feature one carb and a pair of downturned exhausts. After a second trip to Ebay to order some mandrel-bent exhaust sections and a TIG welder, the heavy lifting could begin.

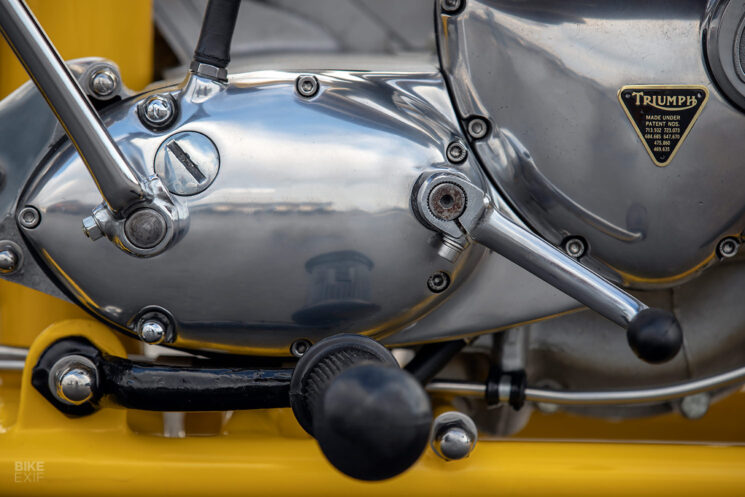

“The first one-off job was to put a unit ignition housing into a pre-unit timing cover, so I had to make a jig from some flat alloy plate that I got from KJE Engineering. I was surprised to find out that most of the bolt holes from each timing cover matched, which made the job a lot easier. So I cut a unit timing cover up for the housing (I know it’s wrong to cut old Triumph parts, but needs must), cleaned it up on my lathe, and welded it into the pre-unit timing cover.”

As the project unfolded, James invented countless workarounds akin to this one. The pre-unit casing had been damaged when someone had tried to knock out the main bearing without first removing the circlip—so he employed his friend Neil to help him engineer a bolt-in bearing retainer. And the unit casing was so badly cracked, that he ended up mating it to half of another Triumph casing; found on yet another trip to The Bay of Dreams.

James’ next mission was to link the engines together—for this, he turned to another friend, Carl Harris of Harris Hot Rod Parts, who lives down the road from him. “I was around his garage for a chat and cup of tea while he was sorting car parts out for a swap meet when I noticed two pulleys for a small block Chevy in a bread crate. After a chat, and £5 each later, I had the start for linking the engines together.”

“I turned the teeth off of two front sprockets and machined them flat so that I could bolt the pulleys onto them. I measured up for a belt and ordered one, but when the belt arrived, the problem of how to take the slack out of the belt was raised. So I went back onto the internet to do some research, where I found an Audi A6 cam belt tensioner—but it had a small roller.”

On the cusp of having his twin-engined creation running, James sent a drawing of the final pulley he needed to KJE Engineering to manufacture. That’s when he hit the first in a series of major hurdles; a worldwide pandemic that shut everything down and stalled the Streamliner project for 16 months.

No sooner had James got the bike back on track, than he hit another brick wall. He was about to order the compact alternator that he had planned the bike’s ergonomics around, but he found out that the company had made an error. “The two-and-a-half-inch diameter was for the section that fits inside the casing. I almost gave up finishing the bike… but I didn’t.”

“I got chatting to Allen Millyard while I was filming with Henry Cole for The Motorcycle Show, and he said he runs most of his bikes on a total loss system, and uses 18650 batteries [cylindrical Lithium-ion cells commonly used in electronic devices]. I emailed some battery companies and only one from Bristol came back to me saying they could help. They said that what I was running on the bike, the battery packs would last one-and-a-half hours—so I ordered two along with a charger.”

Once again motivated to finish the bike, James ordered a pair of brand-new Amal carbs from Burlen Inc., and two electronic ignitions from Tri Spark in Australia. He’d heard that the Mooneyes crew was coming to a local show in a few weeks’ time, so he used that as his deadline. But alas, the Streamliner wouldn’t start—and James had no idea why.

Resigned to the idea that Mooneyes would have to see a non-running bike, James turned his focus to completing the non-mechanical tasks on his list. The bike had been painted halfway through the build by Chris Davison (because James couldn’t wait to see what it would look like), but the yellow frame had picked up some chips along the way. So the bike went to a local body shop, Up to Scratch, for touch-ups, while the seat was upholstered by Custom Coach Trimming. Allen Collins had the task of polishing and plating the myriad aftermarket, modified, restored, and handmade parts that adorn this wonderful contraption.

The bike was put back together, taken the show, adored by all, and then returned to James’ garage to finally troubleshoot the problem. After countless hours spent checking every conceivable point of failure, he stumbled upon the solution online. “I was reading about the café racer boys using pre-unit kick-starters on bigger bored motors, so I thought I’d give one a go. Second kick, and away she went.”

James’ Mooneyes-inspired, twin-engined, garage-built Streamliner is not only a marvel of engineering and a tribute to a legendary vehicle, but also a testament to his imagination, ingenuity, and perseverance, and that of his ever-supportive circle of friends.

“This has taken me seven years to complete and all I want to do now is ride it and show it off,” he concludes. And so you should, James.

Images by, and with sincere gratitude to, Del Hickey

James would like to thank the guys at KJE Engineering, Miles at Autovalves Engineering, Andy Barnett for helping with the welding, and my wife for putting up with me in the garage all the time.