In the rarified world of artisan bike builders, Shiro Nakajima stands apart. His bikes are usually functional, and sometimes even practical: the kind of models a factory might conceivably build.

Some are designed to win races, and others to tackle the occasional dirt road. And then there are the machines that distill the pleasure of motorcycling down to its simplest, most mechanical elements. Like this BMW R75/6, which is almost fifty years old but perfectly capable of keeping up with modern traffic.

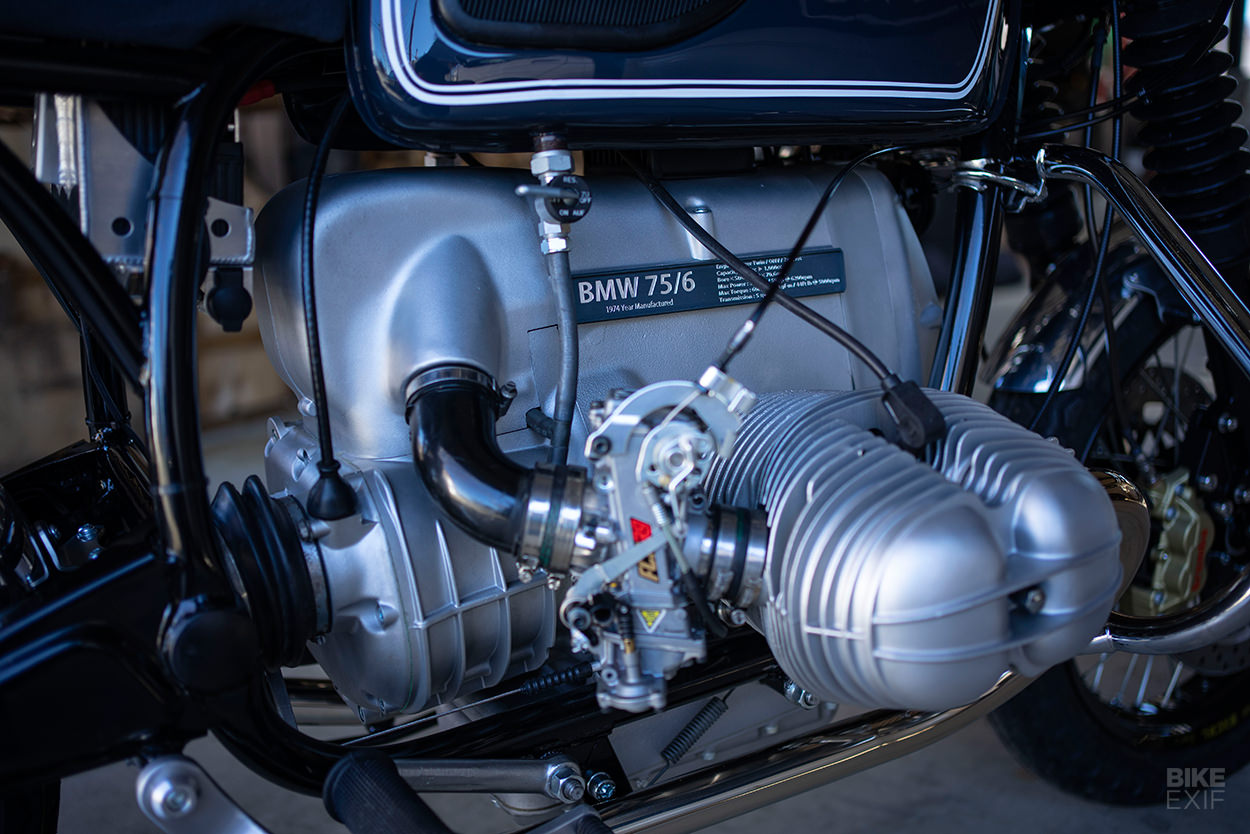

To the untrained eye, this R75 could be a restoration. But keen-eyed BMW aficionados will spot a huge number of well-judged modifications.

“I built this at the request of a customer,” Shiro tells us. “It’s simple and classic looking. But with 1000cc of displacement, a new gearbox and the forks from a Japanese bike, it can enjoy the mountain roads to the fullest.”

When it left the Berlin factory in 1973, this slash-6 boxer had 745cc and a modest 50 hp at its disposal. But when it arrived at Shiro’s workshop, a traditional wooden building on the island of Honshū, the engine was past its best. So Shiro dismantled it, down to every last nut and bolt.

He bored out the cylinders for a capacity increase, installed new pistons, and remodeled the valves and their seating. New big end bearings soak up the extra power and all the seals and gaskets are new too.

The headers are mostly stock, but refurbished and modified at the end to accept new mufflers. Unusually, these are chrome-plated brass, which is only slightly heavier than steel.

The brass mufflers are known for their ‘musical’ qualities—and sold in the Japanese aftermarket for Harley-Davidson fitments. A drilled inner silencer tube moderates the exhaust volume.

The original Bing carburetors are gone, replaced by Keihin FCR39s, which can take advantage of the bigger capacity and help deliver smooth power.

That power now hits the shaft drive via a complete new drivetrain, built from post-1982 BMW components—from the flywheel to the clutch and gearbox. (“The engine response is improved, and shift touch is better.”)

The entire powertrain has been blasted clean, from the gearbox to the engine cases and cylinder heads. Classic airhead motors have never looked so good.

The fuel tank was rusted out though, so Shiro sourced a larger reproduction unit with the classic kneepads, and subtly modified it to fit. The deep gloss paint (and iconic pinstripes) was shot by local specialist Stupid Crown.

The tank sits on the top rail of a modified frame, which has a new rear loop, seat pan and shock mounts. The tubing has been meticulously refinished and cleaned up, and coated in thick black powder.

Shiro sculpted the shape of the seat himself in urethane foam; it’s just long enough to accommodate a pillion passenger, but looks more like a factory option seat than a 21st century custom design.

Two leather seats were then built and upholstered by Razzle Dazzle. The customer can switch them out to suit his taste: one unit has an upper panel in soft gray buckskin leather, while the other is finished with a classic Porsche houndstooth fabric—a favorite of the customer.

So far, so good. But one area where classic style needs a bit of help is in the suspension department, so Shiro has grafted on the 41mm Showa forks from a much more modern Japanese sportbike.

They’re hiding new internals, and are hooked up via Honda triple trees and a custom-built steering stem. The front brakes use Yamaha 300mm discs, plus four-pot calipers and a radial master cylinder from Brembo.

The front end doesn’t look too out of place, helped by the old school rubber fork gaiters—and neither does the back end, suspended by equally old school Öhlins shocks.

The wheels are new Excel rims wired up to restored hubs. This meant machining up several spacers, for accurate fit and alignment, but it was worth the effort. The rubber is Dunlop’s K81/TT100 compound, a modern reproduction of a popular OE fitment on many 1970s bikes.

Muck from the tires is deflected by a pair of aluminum fenders. Shiro has taken regular universal fit fenders, modified the shape and sizing, and hand-made struts and brackets to fit them seamlessly to the fork legs and driveshaft cover.

He’s also fabricated multiple smaller, less visible components like the brake pedal and battery holder [above], which are works of art in themselves.

Simplicity rules in the cockpit though, which sports classic aftermarket bars furnished with Tommaselli grips and a mix of Honda and Kawasaki switchgear. Train spotters will note that the headlight casing and speedo are from a /5 rather than /6 though: a stylistic request of the customer.

To get the headlight to fit, Shiro had to machine up a new bracket. It’s not fabricated from metal, but machined from a block of Duracon, an engineering thermoplastic.

It’s all wired up to a brand new electrical harness, plus a keyless ignition system from Motogadget. And to completely eradicate electrical gremlins, Shiro has also refurbished the starter motor and alternator.

He couldn’t find a taillight or license plate bracket that suited the build though, or complied with Japanese regulations. So he designed and machined up these parts himself, along with a rather stylish fog lamp attached to the engine protection bars.

This is one of those deceptively subtle customs that will still draw appreciative glances in ten or twenty years’ time. And given the solid engineering, it’ll probably still be running smoothly too.

Shiro’s skills also extend into the digital domain: he’s created a mesmerizing video that showcases not only his next-level machining and fabrication skills, but also the workshop equipment and techniques he uses to get results.

The next time you get a few minutes to yourself, switch off the rest of the world and enjoy.