There’s a term that was fashionable in MotoGP racing a few years ago: ‘Aliens.’ It referred to the small group of factory riders who seemed to operate at a higher level than everyone else, with astonishing speed and ability.

The custom world has its own Aliens, and we could probably all agree on the members of that group. But it looks like we have a new entrant: the Canadian builder Jay Donovan.

Jay is no grizzled veteran of the scene (sorry, Craig Rodsmith). He’s a young British Columbian in his mid-twenties, and the man behind Baresteel Design.

He’s based in the garden city of Victoria, and despite his tender years, has a quite remarkable ability to shape metal—a trait we noticed when we featured his Yamaha XS650 a couple of years ago.

Bobby Haas, the founder of the mindboggling Haas Moto Museum in Texas, noticed this ability too. And he gave Jay a commission to build a machine for the museum, with carte blanche on the direction.

“Jay and I cloistered ourselves in his shop and refined a life-sized sketch of what would ultimately become Stingray,” Bobby tells us. “We tossed ideas back and forth all day long, and then I just handed the baton over to Jay.”

The task was formidable, and Bobby knew it. “It is enormously challenging to infuse an e-bike with the aesthetics and romance of an internal combustion cycle,” he notes. “You are deprived of most of the iconic visual elements of a classic motorcycle—carburetors, pipes and so on—and handed a bunch of battery boxes in their place.”

Jay points out that electric motorcycles basically fall into three categories: “A futuristic abstract design, or something meant to look like a vintage cafe racer, or a typical sport bike.”

He started by examining these patterns: “They’re all concepts dealing with the same issues.” And the chief issue? How to incorporate “the design irritation of the ‘brick’.”

On his Yamaha XS650, Jay explored what he calls “fundamental design elements,” but this time he decided to experiment—to disregard standard proportion and geometry. “It meant abandoning the way I usually operate,” he says. “It made the process excruciating for me mentally, but also beneficial in the end.”

The core of Stingray is an ME1507 power unit from the Wisconsin company Motenergy. It’s a permanent magnet synchronous motor (PMSM) with a continuous power output of 14.5 kW.

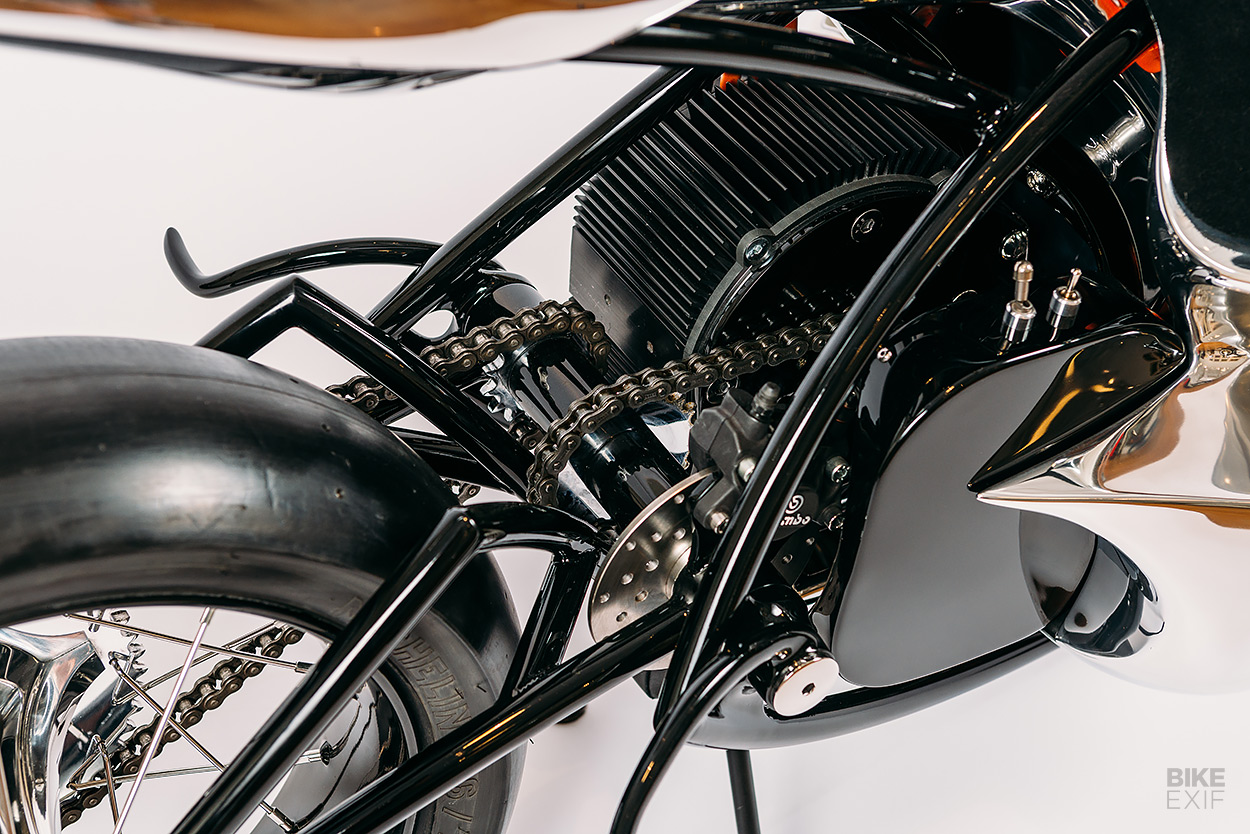

This compact 44-pound motor is now surrounded by chromoly steel, which Jay used to build the frame, forks, and swingarm. Virtually every component is curved on three axes, and uses as few pieces as possible. The looped downtube, for instance, is made from a single piece.

The tighter radii were created on rolling and bending machines, but the third dimension had to be bent by hand—using a torch and steel bucks specifically made for each part. The strength of the frame relies on the abstract triangulation of the curved tubes.

The motor is offset to one side, aligning the drive sprocket with the center of the bike. This allowed room on the other side for the battery management system, as well as a jackshaft located through the swingarm pivot.

The secondary shaft allowed Jay to manipulate the gearing, and decrease the rear sprocket diameter—“Something I thought would take away from the diameter and drama of the front hub.”

The rear hub is another piece designed from scratch, although Jay took inspiration from Max Hazan’s KTM boardtracker. “The rear wheel on that thing was too cool, and I loved the star lace pattern.”

Jay describes the front suspension as a “rather odd trailing-link-springer type setup,” which is supported by a FOX mountain bike shock. “I knew I needed to keep the forks as narrow as possible, to allow for steering clearance underneath the low hanging fairing.”

Jay’s designed the front hub with an internal rotor, dual Brembo calipers and two large discs: “They’re essentially wheel spacers, but act as a visual focal point for the forward leaning body … I used the discs as a pickup point for the front suspension linkage, so the entire linkage system could be contained between the fork legs.”

The wheels were custom made for this project by Stephen Hood at Vintage Rims in Australia. “They were designed to resemble the simplistic appearance of an old clincher rim,” says Jay, “but built wider—and with an edge bead designed to hold modern tires.”

The battery packs are concealed behind the sculptured aluminum. This is .080 gauge mostly, in 5052 rather than the 6000 series we usually see. “It’s a bit tougher than the usual .063 I have been using, but I thought I would have a bit more material to work with for filing and block sanding,” says Jay.

The seven battery packs are spread around the bike: three in separate boxes running down the center of the bike, and two contained in large single packs on either side. Each battery was hand assembled with the help of Chris Jones at Voltron in Australia and it’s a 100-volt system.

Each pack contains 56 individual lithium cells—four in series and 14 in parallel. “The batteries are installed in the packs so that heat can diffuse through the surface area of the sculptured shapes,” says Jay. It’s a good way to disrupt the problem of ‘brick’ aesthetics.

There’s a compact Sevcon Gen4 motor controller mounted underneath the ‘gas tank,’ and to cool it, there are two intakes at the front of the tank. The back half of the fairing also creates intakes, which direct airflow down into the hollow underbody and out via the tail section. There are further concealed tunnels inside the body of the bike to keep air flowing around anything that heats up.

The whole machine is essentially a play between form and function, executed by a builder with tremendous skills. “I gave the most thought to the relationship between those two elements,” says Jay. “It’s a conscious experiment to refine my design abilities—so form and function each complement the other.”

The jaw-dropping looks of Stingray and its clever packaging suggest that Jay has succeeded. It also oozes quality, with immaculate surface finishing and clever detailing.

“I was trying to understand what quality really means, in a physical and personal way—and how it correlates to advancements in technology,” says Jay. “That’s not exclusive to electric vehicles by any means, but it’s why I felt so strongly about using electric power.”

Jay obviously spends as much time thinking about his bikes as he does with a dead blow hammer in hand. “There is a sensitivity and a philosophical side to Jay that I’ve rarely seen in my seven decades of life,” says Bobby. “Often when we chat, it’s not about motorcycles, but rather about life—and where the world is headed and what our role is in this industry.”

We asked Jay what his next build will be, and it’s going to be a collaboration with vintage motorcycle expert Paul Brodie. They’re building a bike around a 1919 Excelsior motor, to mark the 100th anniversary of the famous racing marque. As a project, it’s a 180-degree opposite of Stingray.

If you’re keen to see Stingray, head over to the Haas Moto Museum in Dallas. But it won’t be in the main display area just yet. “We have a space just outside my office for one motorcycle,” says Bobby. “Museum director Stacey Mayfield and I can stare at it all day long.”

“And that’s where Stingray sits.”

Baresteel Facebook | Instagram | Haas Moto Museum | Images by Grant Schwingle