Photos: Jun Song / Film: Max Daines

It’s one of the most unlikely alliances we’ve ever seen: An old school machinist and motorcycle builder from Utah, and a high-tech industrial designer from Istanbul, Europe’s most populous city. But there are few boundaries to communication in the 21st century—and together, these two kindred spirits have created a truly extraordinary motorcycle: the BMW-powered ‘Alpha.’

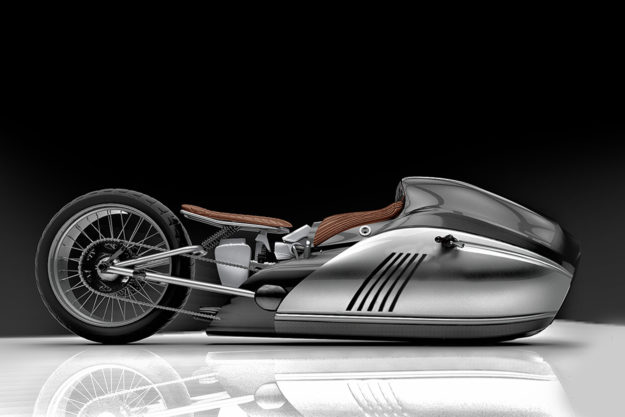

The story starts in Turkey on the computer of designer Mehmet Doruk Erdem. Nearly two years ago, Mehmet posted his BMW Alpha concept online: An arresting, shark-nosed land speed racer.

Mehmet caught the motorcycle design bug after seeing the machines ridden by the legendary Bonneville racer Alp Sungurtekin, the man behind the world’s fastest Triumph pre-unit.

“I started to make models of Alp’s motorcycles,” says Mehmet. “Then I saw the film The World’s Fastest Indian. I was ready to design motorcycles for the Bonneville Salt Flats.”

One of those designs was Alpha, which has a clear visual link to the most infamous marine predator of all. “Great white sharks have always been an inspiration to me,” says Mehmet. “So I decided to mimic their anatomy for Alpha’s bodywork. It had to look powerful and beautiful at the same time.”

“If you look at the body of a shark, you can see that it’s clean and perfect. But inside, it’s so complicated. So Alpha’s front end is clean and smooth, while the back is the powerful and ugly side—symbolizing the tail of the great white.”

“The rear has to show where the power comes from, whereas the front is about aerodynamics. There is no connection between those two styles. The rider must be the connection between beauty and the beast.”

Word was spreading of Mehmet’s amazing designs, and bike builder Mark ‘Makr’ Atkinson became a fan. “I’d seen a couple of his designs online,” Mark tells us. “Then my father posted a picture of the Alpha concept on my Facebook page. It was good timing: Racing on the Bonneville Salt Flats had been canceled again, and I needed a winter project.”

Mark (above) normally builds a new race engine every winter. And when we say, “builds an engine,” we don’t mean he goes shopping for parts online. He starts with a big billet of solid aluminum and designs an entirely new engine. Apart from the seals and bearings, he makes everything—right down to the cranks, conrods and pistons. (It’s taken him a few years, but with the help of other two-stroke tuners, Mark’s current Yamaha makes world-class power.)

There was no racing to be had, though, and Mark was cooling his heels. He became obsessed with the Alpha concept, and wondered: What would it take to turn those sleek concept renderings into a functioning motorcycle?

“I had a wrecked BMW K75 and hauled it to work,” Mark remembers. “My boss at S&K Machine—who is also a motorcycle guy—said ‘Get that out of here! We’re a machine shop, not a motorcycle shop.’ I told him I’d only need a couple of weeks to figure out a chassis…”

Then Mark hit a road bump: He couldn’t make contact with Mehmet, even through Facebook. So he went ahead and started building Alpha anyway.

At this point, Mark was focused on the underpinnings of the bike. “I got the chassis done over several months. My bosses started to see the greatness coming out, and were soon parading customers into the weld area to show it off. Sam and Alber deserve a shout-out for allowing Alpha to come to life in their shop.”

The hours were long. Mark’s job occupies up to twelve hours a day, but afterward, he’d carry on for another four or five hours on Alpha.

His process is methodical rather than ‘big picture.’ “I let the problems surface and then work through them, one at a time. The whole picture is too much. I plan the total as an abstract distant goal but focus on each individual component. As I go, I design parts and pieces.”

“In the end, I have every piece modeled, so I can modify it if I need to. I often redo parts over and over, until they are just right. I let the bike organically find its own way: That took years to understand. Bikes have their own personalities, you just have to let them out.”

As he approached the body fabrication, Mark started to feel ‘weird’ about building someone else’s design. “I reached out to Mehmet again on Instagram and Facebook. There was no response.”

Mark abandoned the idea of building Alpha and researched alternative styles. “I took inspiration from Paul Bracq, the BMW auto designer in the 1970s. My design was okay,” he says, “but it wasn’t Alpha.”

Stuck at a frustrating crossroads, Mark made a last ditch effort to contact Mehmet. And this time, a message came back.

Mehmet explains: “I didn’t respond at first because, too many times, people have asked me to start a project and it went nowhere. Then I saw Mark’s images—he had already started! So I believed that he would share my dream, and make it real.”

From then on, it was pedal to the metal. “We started to share everything about the bike every day,” says Mehmet. “I think it took around 16 months to finish. From Utah to İstanbul, we worked together to make Alpha more beautiful.”

During his lunch breaks, Mark would send Mehmet pictures of his progress on the bodywork, and the designer would return with feedback. “This interaction could have never happened thirty years ago,” says Mark. “Two guys with differing ideas, coming together for a common goal. A Mormon and a Muslim, across the world from each other. We’ve become friends.”

When Mark sent pictures of individual parts, such as the saddle, Mehmet would model and refine them in 3D programs. “Mark is a great machinist. The way he looks at details is amazing. He wants everything to be done in a perfect way.”

Then Mark started making a plug for the body. “I bought every book I could find, and watched tons of videos. I bought a bunch of sheets of hard foam insulation from the hardware store and glued them together, layer by layer until I had some semblance of a shape. “

After months of sanding and eight gallons of filler, the plug was finished. “I called in every guy I work with and asked them to tell me what they saw. I was too close to the project, overly optimistic on some points and not paying enough attention to others.”

“Even with body contour gauges, I was all over the map. But the shop foreman became invaluable to me. He told me when the curves are wrong, and then finally when to stop. Chad Esplin, I owe you a big thanks!”

“When it was time to pull the mold, it was back to the books and YouTube. I gathered the materials from all over the US. It cost much more than anticipated.”

Mark started spraying gel coat, and the workshop filled with a horrible chemical odor. (“Payback on this is going to be harsh…”) But the mold came out much better than Mark expected—as symmetrical as his eyes could see, and the troublesome gills were fine.

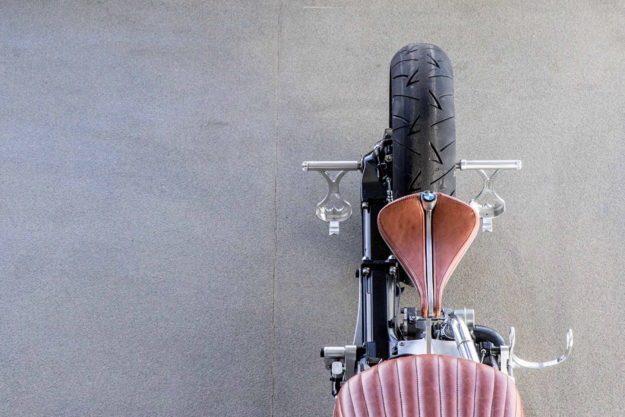

It was time for a break, and to look at the engine and transmission. Mark had the head rebuilt and fitted new seals, and finished it with fresh paint. “It went back together like a BMW does. My love of BMWs is from the inside out; They stay with a similar design for years.”

“This engine is very much like the M10 through to S52 car engines that I have experience with. They use fine thread fasteners and correct length bolts. The parts are machined to exacting tolerances. I’ve been building engines for a long time, and BMWs are by far my favorite. They design like I design.”

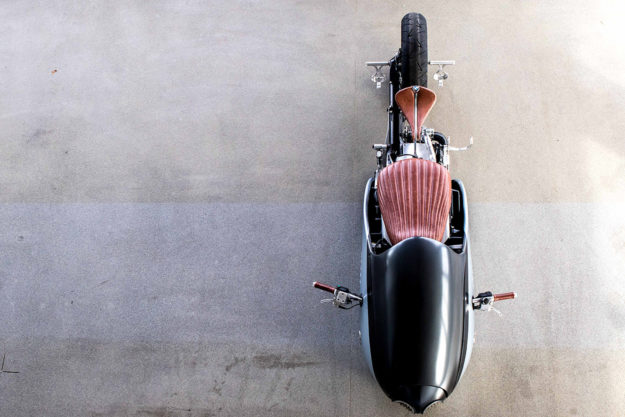

It was time to complete the body and, in a surprising move, Mark chose to use basalt. “It’s a lava rock that’s extruded into string and woven into a cloth, like carbon fiber. It’s an unusual and very beautiful natural fiber.”

Via a dealer in Germany, Mark bought what he thought would be enough material. But it wasn’t—not by a long shot. So he tracked down a skateboard guy in Canada who offers a basalt/carbon cloth and tried that.

“I used four layers. It came out so flimsy it was unusable. I tried again, but this time with seven layers and vacuum bagged it to squish out the excess resin. It worked pretty well.”

Given the cost of the materials, Mark was anxious when it came to tackling the nosepiece. This time the vacuum bag didn’t seal well, and the resin didn’t set. “I had no idea why. I called the resin guy, and he said I’d used the wrong resin. I told him: You sold it to me!”

“I find that composite specialists do not give away their hard-earned secrets. It cost me plenty to learn that. But for me, the point of building is learning. If your goals in building are for reasons other than personal growth, you are missing the point.”

“I don’t just mean the learning of specific skills—it’s learning how to deal with frustrations and setbacks. Those are skills you cannot get from books.”

Mark ended up using four layers: two of straight basalt, with two of the basalt/carbon mix sandwiched in the middle. But now, the gills were giving him trouble.

Help came in the form of a friend, Brittany Backer, who told Mark he needed to pleat the vacuum bag between the gills. “I asked her how she knew this. She said, ‘You know what I do, right?’” Turns out that Ms. Backer works at Boeing, laying up vacuum bags on the wings of 777s.

The balance of the bodywork is just ‘right.’ And it’s not too pretty: the tension between the front and back gives the bike an amazing presence. By explanation, Mehmet points to Francis Bacon’s essay Of Beauty from 1612, and one quote in particular: “There is no excellent beauty that hath not some strangeness in the proportion.”

Mark entrusted the seat and upholstery to Eli Scarbeary, who he bumped into at a local motorcycle meet. “Eli did an excellent job. When I went round to pick up the parts, I saw at least three other abandoned seat covers on the ground. He had to work at this.”

The paint Mark handled himself. “I am average—I paint like I weld. Around the time I finish a project, I get the ‘feel’ back, until I do it again a year later. I think it’s both a curse and a blessing to feel the need to do everything myself.”

The idea of using the famous BMW ‘kidneys’ had been floating around in Mark’s head since the start. “I think the BMW 328 Mille Miglia is one of the most beautiful cars of all time, and the kidneys on that car stuck in my mind.”

He formed the kidney inserts with a bag and hammer and then planished them, getting them close to the contours of the nose section. Mark then cut the inserts to shape and welded in small pieces at 90 degrees. “I have 40 hours in those two parts,” he says.

The nosepiece hides a center hub steering setup, based on a 2007 patent that Mark found online. Designed by the engineer Jean Michel-Theirs, it uses a pair of tiny hydraulic cylinders for activation.

Alpha, remarkably, could probably be made street legal: It has lights, turn signals, and a horn. “It is pretty un-user-friendly,” Mark admits wryly, “so it won’t get ridden much. But I have lots of bikes to ride, so this is just fun.”

All that was left was the wiring and final assembly. “It went together like it should. No great stumbling blocks, other than waiting for parts. It fired right up and idled like a BMW should.”

“Over the course of building Alpha I have learned a lot and have made new friends,” says Mark. “But is it my greatest achievement? Naw. Building an engine from scratch and setting a land speed record the first time running would be—but Alpha is a very close second.”

Some guys are just on a whole other level.

Mehmet Doruk Erdem | Mark ‘Makr’ Atkinson

From Mark: I want to thank lots of people that were helpful. The guys on the ADV rider forum were a great sounding board, and gave terrific advice. Almost everyone I showed the concept picture to was over-the-top happy to help make Alpha real.

David Tagg who does my tires at Wrights motorcycles, and Tim who owns Wrights were especially helpful. Dave mounted and remounted so many tires, re-lacing the difficult BMW spoked rear and my goofy front wheel several times.

My long-time friend Cougar at Luxe Auto Spa let us do photo shoots, detailed Alpha, and always had my back. Jun Song spent several days doing photo shoots through this, and Max Daines and Nico Cages did the video. But mostly I want to thank my son, Garrett, whose calm demeanor kept me sane.

The next challenge awaits…