I’m a photographer of many things. I shoot live music, portraits and fashion, but my favorite subjects have wheels—and more specifically, two wheels.

There are many ways to photograph a motorcycle. You can shoot it while riding, racing, or wrenching. Or when it’s just leaning on the kickstand at a show. But most of the motorcycle photography I do is for publications such as Bike EXIF, and the objective is to get a very clean, well lit, and uninterrupted view of the bike and its details.

So I’m going to walk you through the process of getting good, clean shots, without using a studio or expensive ‘pro’ equipment. These are simple guidelines, not rules, and they can be broken from time to time. But they’ll get you started, and help you get ‘that shot.’

A word about gear The camera you shoot with is never the most important thing. You do need the right set up, but it doesn’t really matter whether it’s a $300 eBay bargain or that darling of the pro photographer, the Canon EOS 5D Mark IV.

Any DSLR with a lens of 50mm or more is a good starting point. In general, it’s easier to blur the background on a DSLR than a compact camera. The most important point is to avoid shooting at a focal length of less than 50mm on a ‘full frame’ DSLR, unless you are deliberately aiming for a distorted wide-angle effect.

There are two reasons for using lenses extending beyond 50mm, like the ones shown above. Firstly, shorter focal lengths distort the dimensions and proportions of the bike, such as making wheels look slightly ‘out of round’ when shot from side-on. Secondly, the longer your focal length, the easier you’ll find it to isolate the subject from the background. (You’ll also get a compressed perspective effect when shooting the bike at ¾ angles, which flatters most bikes.)

I usually shoot with a fairly open aperture, without going so wide that parts of the bike go out of focus. Somewhere around f/4 often works best.

Get your timing right The first thing to figure out is what time of day you’re going to shoot. When shooting outdoors, you’re usually better off shooting when the sun is lower and less harsh—which means very early in the morning, or late in the evening.

At these times the light is more even, and the top of the tank and polished metal parts won’t be too bright. If you must shoot with a high sun, try finding some open shade.

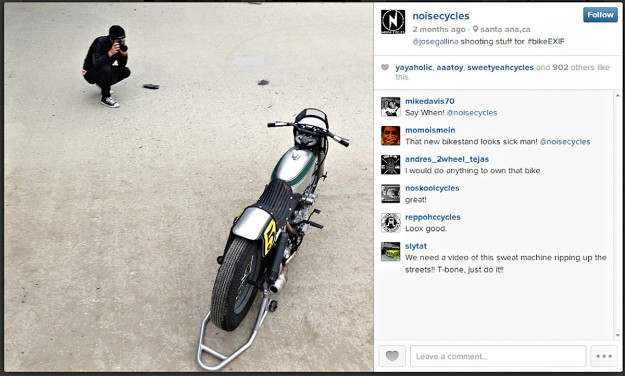

Although we woke up before the sun to shoot Noise Cycles’ 1952 Harley Panhead ‘Sneak Attack’ (above), it took us longer than expected to get to the location. Luckily there was a bridge overhead that gave us perfect open shade.

Background checks When you’re deciding where to position the bike, check out what’s behind and how it works with the lines and colors of the bike. Try to find something that contrasts slightly in color with the bike, which will help your subject stand out.

Avoid things with too many heavy or strange lines, such as a rod iron fence. Be wary of telephone poles and trees, which may appear to be growing out from the bike. I like to use industrial garage doors, brick walls that aren’t too ‘busy,’ or just an open field and clean sky.

Here’s a good example of what not to do in motorcycle photography. There are lines all over the place, distracting and interfering with the lines of the bike. And the bright orange garage doors detract from the more subdued burnt orange panels painted on the bike.

Let there be light We’ve already touched on the need for even light, but I want to show a trick to boost it a little. Getting light into the right places is especially important in motorcycle photography, because on many bikes the tank tends to throw the top of the motor into shade.

You can get around this by using a big white board to redirect light into areas that need it. Try it—it’s an easy and cheap alternative to pro lighting rigs. In the shot above, I simply propped up a white board with a stick. Looking through the viewfinder, I could see a difference immediately as the light filled in.

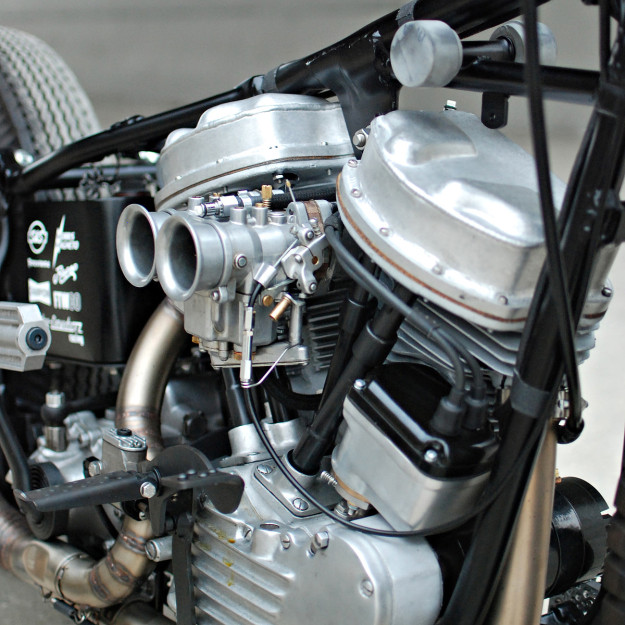

All the angles Have a checklist to hand before you start shooting. Get all the basics: Left, Right, Front, Back. Then start going for the details. Shoot the major components: the bars, the motor, the seat, the tank and the pipes. Ask the owner or the builder to point out elements that they want to highlight on the bike. And although close-ups are less affected by the background, stay mindful of what is ‘in shot’ and in focus at all times.

Nowadays, with digital, it’s easy (and cheap) to shoot away. So once you’ve got the basics of motorcycle photography covered, use the rest of the time to explore the bike. Find the most interesting details, and experiment with unusual angles. In the image above, I’m looking for a viewpoint to capture the tank and bars of the bike.

For this image of the Panhead’s motor, we actually removed the tank in order to show the whole engine.

Low down and dirty The biggest thing that will set your shots apart is your own angle. Most of the shots people upload on to Flickr, Instagram and Facebook are taken from the standing position, using a point-and-shoot camera on its Auto setting, or a smartphone.

This works as a simple record of a bike, but your objective is to make the bike look good. And that means squatting down or sinking to your knees, like I’m doing above. Lower your eyes and camera to the level of the tank or headlight. It’s the one trick that makes any bike look much better.

Back at your desk This is where you really get to refine that shot. Even simple photo editing software will have some tools to perfect what you’ve shot. I use Photoshop and Lightroom: both work great, but Lightroom (below) is all you really need—and you can get it for around $10 a month.

After loading up the image, check for areas that are too dark to show any detail, and lighten them up. It could be a black leather seat, or the tires, or darker parts of the motor.

Make sure the bike and horizon are level, unless you are deliberately going for a dramatic ‘Dutch angle’ effect. Slightly crooked photos mess with people on a subconscious level: most people won’t know why, but something won’t feel right.

Don’t be tempted to crop the shot too tightly around the bike. Leave ample space, which is especially important if the photos are going into print and will be laid out with text and other photos on a page.

Never stop shooting (and have fun) After you’ve shot your own bike, move on to a friend’s bike, or contact a local builder. Seek out different locations and examine your results. You’ll soon get a feel for what works and what doesn’t. Keep shooting until you like what you’re getting from your camera, and you’ll find yourself enjoying the process.

For me, the best part of shooting new bikes is meeting new people, and spending a few hours talking about (and gawking at) motorcycles. You’ll often get the occasional stranger coming along: In the shot above, Scott Jones of Noise Cycles and a downtown Santa Ana, CA local had a good time chatting about the “Good old days, being wild and young on the back of a motorcycle,” and looking over the bike.

So go out and shoot, and remember, these are guidelines and not hard-and-fast rules. The most important thing is to enjoy your own motorcycle photography.

Head over to Jose Gallina’s website to see more examples of his work.