‘Now that it’s out and running, be sure you run it,’ the 1951 Ariel’s owner said with a wink before sending me on my way, but I was feeling out of my element riding the Ariel Square Four. The shifter’s on the right and shifts backward, feedback from the brakes is vague at best, and the engine was puffing smoke since waking from hibernation.

‘I’ll just tool it around for a bit,’ I thought. But the character of this peculiar four-cylinder revealed itself on the open country roads—and what a lovely alloy lump it is.

It may seem like an oddity today, but a 2×2 four-cylinder engine was definitely a novel concept when Edward Turner first sketched the idea in 1928. Working as a motorcycle dealer and building bikes of his own on the side, Turner wanted to design a next-generation powerplant with higher output and long-haul touring ability. There was a stigma against four-cylinder engines, though, in that transverse fours were considered too wide, and longitudinal engines were too long.

Taking inspiration from your average twin, Turner designed a four-cylinder consisting of two parallel twins in a single case, with one right behind the other. And while it sounds a bit complex, the idea had merits far beyond the packaging, as the counterrotating cranks and four pistons would offset each other and run quite smoothly.

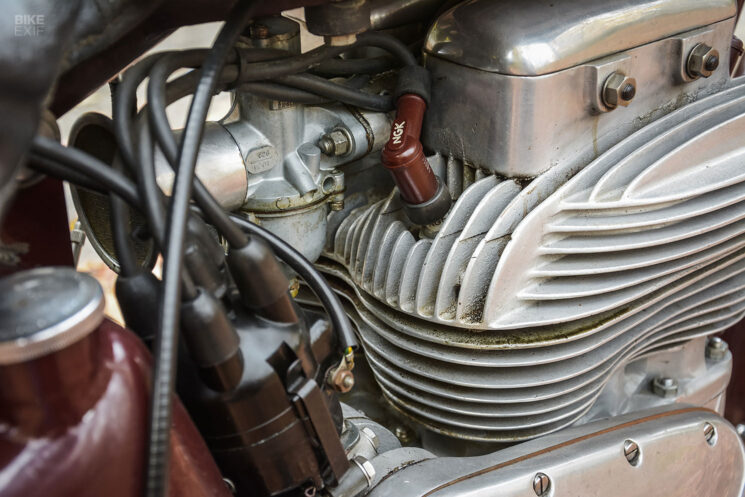

And that’s engineering theory at work, as the Square Four is a really smooth engine, even compared to more modern bikes. While it ticks incessantly and sounds a lot like a Farmall tractor at idle, the Square Four really comes into its own with a little rpm. There’s no tach to report rev increments, but the engine offers brisk and steady acceleration through corners and up to highway speeds, and must have felt otherworldly to ride when it was new.

Turner found a home for his square mill at Ariel, and after reworking his prototype significantly to reduce costs, the 498 cc, OHC 4F Square Four was unveiled in 1930. The engine was so compact that it fit in the standard 499 cc Ariel Sloper chassis with a Burman four-speed transmission, and provided splendid performance.

The 4F model would go on to win the Maudes Trophy in 1931, and a supercharged Square Four achieved a blistering 110 mph at Brooklands. Capacity was increased in 1932 to 601 cc to handle side-car duty, but faults with the initial cost-cutting design were becoming evident.

The updated 4G model emerged in 1936 as an OHV 995 cc machine with an improved cooling fin design to alleviate severe overheating issues on the rear cylinders. In 1949, the new Mark I was debuted with alloy cylinders and cylinder head, allegedly cutting 15 pounds in the process.

The final Square Four model, the 997 cc Mark II, would feature a completely redesigned cylinder assembly and four separate exhaust headers, and was capable of 100 mph off the showroom floor.

Just about any Ariel is a hot commodity today, and given the unusual engine geometry, test riding an Ariel Square Four isn’t an opportunity I’d pass on.

Built in 1951 as an alloy Mark I, this particular Square Four was no show queen, but still a desirable piece of old iron, and I couldn’t ask for a better autumn day to travel back in time 70-some years. The Squariel fired to life with relative ease after topping off the battery, and the sound is unlike any four-cylinder you’re used to.

Beyond just adjusting to the controls, the Square Four has interesting ergonomics that places the wide fuel tank right up in your business, and your feet back a bit to reach the pegs. It’s also not a large machine, and after heaving its 440-pound heft off the center stand, I was surprised at how small the bike felt on the road.

Getting up to speed, the Square Four driveline is certainly one that’s designed to be ridden in a spirited fashion, and if you attempt to just lug it along, things get a bit clumsy. The engine will lug or rev as you see fit, but to get smoothly through the gears, it wants a little rpm. Shifting requires a deliberate movement of your whole right leg, rather than just your foot, and without a quick and thorough push of the shifter, you’re sure to be met with a cringe-worthy grind from the gearbox.

As I grew more comfortable with the Ariel, my hesitation over the electrical-taped throttle assembly faded, and I was rewarded with the sweet sounds of acceleration from the twin chromed exhausts. I couldn’t stop thinking how the Square Four feels like the bike equivalent of an old 911; primitive in ways, but pure and thrilling.

The stunning Smiths speedometer climbs in steps like the second hand on a watch, and clunking into fourth gear, the engine hums pleasantly at highway speed. I can’t say the same for the chassis though.

There’s nothing like a corner to keep you in check, and a bend on the Ariel comes with the requisite mental verification of which direction to push the slushy shifter. Despite some looseness in the lever, the front drum works more or less as intended, but the rear brake is a real zero-to-100 sort of affair. Also, should I have verified the date codes on these Avon tires?

The bumps are another solid reminder of how much engine design exceeded chassis and suspension technology of the day. This Mark I Ariel is fit with a standard telescoping fork, a plunger rear and a sprung saddle.

Point is, no part of the Ariel chassis moves in harmony after you hit a bump, and both ends do their own thing on their own time. Also, all but the smallest crack in the pavement bottoms out the saddle springs—not in a spine-compressing fashion—but you’re well aware coil bind has occurred.

Returning to base with the Square Four was more-or-less a drama-free affair, and despite how unusual the bike is, I felt as though the general public took little notice of my backroad shenanigans. Even with the idiosyncrasies and little quirks in handling that come from the passage of time and technology, the 72-year-old Ariel is still a bike that works in our modern world.

You can meet or exceed traffic on any road, and you’re reminded of dedicated souls who built, resurrected and preserved this classic Brit bike when you hear a squeak from the brakes, grind from the gearbox or cough from the carburetor.

And that’s a feeling you won’t get from anything with a catalytic converter or ABS.