What’s the best part about the exploding interest in older bikes? For us, it’s not just about the finished product and the photographic eye candy.

It’s also seeing traditional skills staying alive: Lathes whirring, English wheels spinning, and planishing hammers hitting metal. And it doesn’t get more authentic than this ancient French resto-mod, brought back to life in the English countryside.

This extraordinary machine is a Motoconfort C23, which looks like it was built yesterday but is actually 84 years old. It’s the work of John Harrison, who at 63 is just a wee bit younger.

John lives in the old medieval market town of Dartford, in southeast England, and he’s been making a living as a mechanical engineer since his boyhood days.

We got the tip-off from his son Mike, who describes his Dad as “One of those old school engineers that can make things out of lumps of steel, with dangerous looking machinery, after sketching it on the back of a cigarette packet.”

As you can imagine, getting an old French bike back on the road isn’t simple. You can’t just pick up a Motoconfort parts manual and trawl through the classified ads. But John wanted a challenge, and is particularly partial to girder forks. When the Motoconfort popped up on eBay France, he knew he had his next project.

It’d had two previous owners, and the last one had stored the bike with the intention of rebuilding it. That was in 1959, and it never happened. “It was pretty mangled and rotten,” Mike recalls. “But it was reasonably complete—making it easier to make new parts by copying the old.”

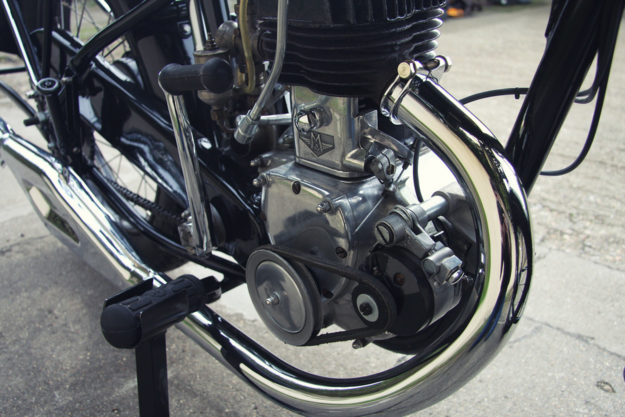

So John took the Motoconfort apart, and if he needed to replicate or modify a part, he created it himself. He’s one of those multi-talented guys who are a dab hand on a milling machine, lathe and cylindrical grinder.

“He won’t stop at the bare essentials though,” says Mike. “He might say, ‘It could really do with a choke,’ and then, well, he’ll just make one for it.”

“Why not, eh? I could write out a list of the parts he made, but I think you get the idea.”

John handled all the welding, brazing, panel beating, prep and paintwork, although he copped out with the magneto—sending it off to France to get it repaired.

There are ‘new’ parts throughout, although you’d need to be a Vintagent-level motorcycle historian to spot them. John has remanufactured the fender stays, and a multitude of bushes, gaskets, cables, mounts and linkages throughout. Plus the hand controls/levers.

The forks are restored back to original spec, and the wheels are pattern rims rebuilt with stainless steel spokes, now shod with Avon Safety Mileage Mk II rubber. Everything else has been sand blasted, straightened, sprayed and re-chromed.

The frame was frankly troublesome. “Plenty of bending, brazing and welding was required,” says Mike. “The rear rack was incredibly tricky to straighten out. Then it was sprayed in acrylic paint.”

The modern touches are very subtle: there’s no Gixxer front end grafted on here. The lighting has been upgraded, with custom parts around the headlamp assembly and an aftermarket rear light that still looks original.

And when John was forced to make new fittings or brackets, he often manufactured them with modern metric threads.

Was it all worth it? Oh, yes. “When it starts, It sounds fantastic,” says Mike. “But riding it is a joy and a nightmare. There’s a suicide gearshift, a foot clutch, and levers instead of a throttle.”

“It’s definitely not for the faint hearted.”

These are the kind of stories we love, and we’d link to John’s website if we could. But he hasn’t got a website — “because you can’t make one with a milling machine.”