In the short time that the BMW R nineT has been around, it’s established itself as a strong contender in the heritage segment. And now the Scrambler’s landed in showrooms—the first nineT derivative, with a reported two more on the way.

The R nineT is actually a bit of a departure for the German über-brand. Their bikes are usually at the forefront of tech—like the continent-devouring tour de force that is the R 1200 GS.

It’s been like that for years: the R 100 RS sported the world’s first air tunnel-tested fairing. And the R 80 G/S launched the large capacity adventure bike.

So why build a heritage bike? And why use an air-cooled boxer motor, when you have a newer, liquid-cooled model on hand? More importantly—how do you measure how good it is, when it’s not based on numbers?

We sat down in Munich with the guys who have the answers: Ola Stenegärd (Head of Vehicle Design and Creative Director of Heritage), Roland Stocker (Heritage Project Leader, below left) and Thrass Papadimitriou (Heritage Business Development Manager, below right).

We spoke about the development of the R nineT and the Scrambler [review], how the alt-moto scene is getting more people onto bikes, and Ola’s cats.

Bike EXIF: BMW are known for building bikes that are very measurable. How did you transition from that mindset, to building bikes that are emotional—like the R nineT?

Roland Stocker: As you say, in Germany everything is very measurable. And we are used to building motorcycles for the kind of people who measure things—who are really looking at tests, counting numbers and looking at comparisons.

But we found there’s much more in the world outside. Especially if you look at these guys who like customizing old Beemers—they don’t look at stopping distance, at acceleration numbers. They have the emotional side.

This made us think different. Because we have to build a bridge for these people to the modern world, and this is what drives us with the R nineT—it helped us to begin looking at the emotional side.

Thrass Papadimitriou: You have both sides of the card: you have guys who still like performance, and who are very focused on numbers. But what you see growing—and this is also where Bike EXIF comes in—there’s a lot of people who look more for character, they look more for aesthetics, they look for other features in the purchase of a motorcycle.

What is new to us, as a company, is how do we make emotional bikes? Why do we still want the old engine? By having the liquid-cooled engine but at the same time keeping the air-cooled boxer, you will address these different types of customers.

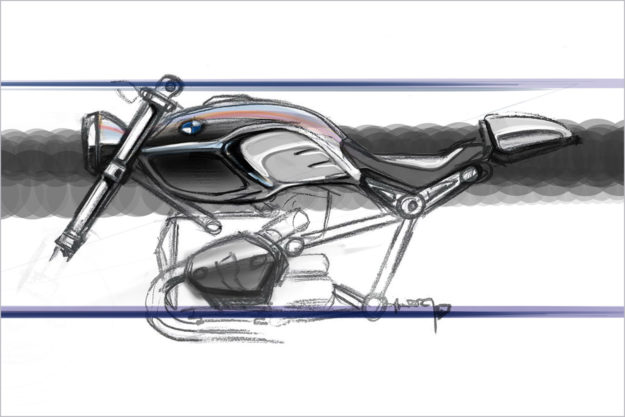

Ola Stenegärd: Having it air-cooled was super important for us. We’re all from the scene, we all know how important the air-cooled motor is—and the simplicity when you customize it.

But at the very beginning of the nineT it was really hard to get numbers together. We’ve been in the custom scene for a long time, now all of a sudden we saw something was growing, and starting to take shape out there. And we said: “There’s definitely space here for a bike from us.”

But, of course, it’s very hard to put a business case together just based on a couple of opinions from some weirdos in the company. So we really had to get the numbers together. But I also remember Bike EXIF started to explode back then. And we also used that as a point.

So who drove the project then?

Ola: You have different ways of starting projects at BMW. Either it can be very calculated: you have a very long strategy phase and you look into the markets. Like the S 1000 RR—we wanted to have a bike in this segment, and in order to be in this segment you have to achieve this, this, and that.

And then there are other products that happen very organically within the company. I always call them ‘internal garage projects’—just a couple of guys that say, “What if we do a bike like this? That would be pretty cool!”

And if it’s a really good idea, you can show it to the motorcycle board, and if they also like it they can make a tick in a box and you can continue to develop it. The original GS was actually done like that—that wasn’t calculated at all.

The nineT was like the GS. We were just, like: “Dude, it would be so cool to still have an air-cooled boxer that’s super minimal, and really cater to these guys that just like the pure riding experience, super simple, as an alternative.”

Thrass: At the time, the CEO of BMW Motorrad saw the concept and he really believed in it. You always need a bit of the top guy basically saying: “You guys go ahead.”

Are you referring to the Lo Rider? Was that the birth of the R nineT?

Roland: Yes, the Lo Rider. It was the DNA. Mr von Kuenheim saw this bike, actually somewhere in the corner—

Ola: It was in the basement.

Roland: —in the basement, when he started at BMW Motorrad. And then he said “Wow, this is a cool concept—what are you doing with this?” There was no real plan, so he said, “Let’s try it as a test balloon, put it at EICMA and see how the public reacts.”

It took another two years to tell the markets about the idea, and to figure out how to do it, and to explain it more in detail. Because they did not really understand this concept.

Do you think you were a bit early with it perhaps?

Ola: It was also about getting numbers. Even with the marketing guys—the feedback was great… but the feedback was going in a lot of different directions. A lot of people liked it. Some guys were saying, “I love it because it’s like a street fighter.” Then someone said “oh, it looks like a classic… it’s super cool, I want it!” So they had so much split feedback, they couldn’t make any sense out of it. You know, in ‘measurable’ terms. But they all said they loved and they wanted it.

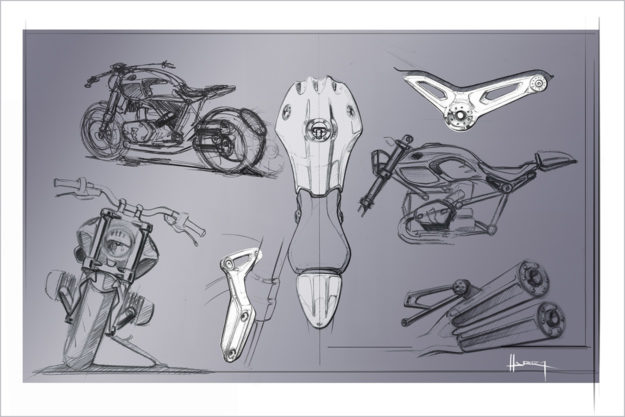

How did you get from the Lo Rider to the R nineT—was it very different from, say, sitting in your workshop and building a custom bike?

Ola: A product like this, not much. We worked exactly like that, kind of unorthodox.

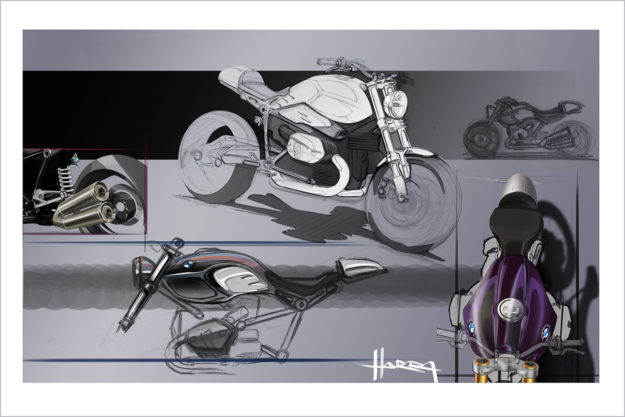

The concept bike was a bit rough around the edges. And normally you can never achieve what you do in a concept bike. The production bike is always gonna be a little bit ‘less’ than the concept. And we just said right away: “No, this time we’re gonna do it the other way around. This bike is gonna be better than the concept bike.”

Roland: This was actually the first time that a production bike was better looking than the concept bike.

What was it like making aesthetic calls on aspects of the bike, rather than aiming for outright performance?

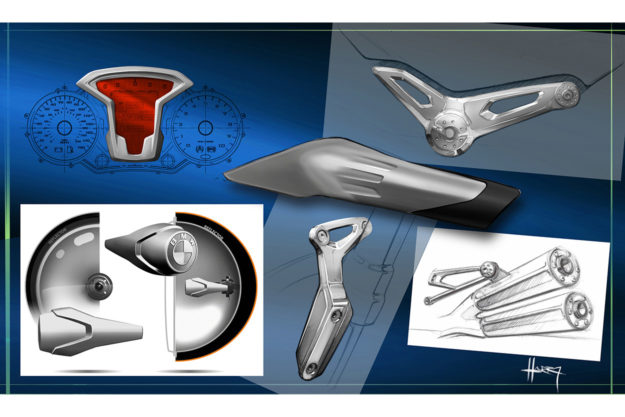

Roland: It was a completely different approach. For example, with the R nineT, we have different options for the exhaust. So I did a different exhaust in a different shape, and the aftermarket people from BMW asked me: “So what’s the benefit? Does it have more performance?”

No. It’s the same horsepower, but it’s the style and the noise. The look and the feel—this is what we are trying to change, and to make it more individual and different. So sometimes you get a big question mark when you tell it to people who are used to working with the GS side.

Ola: It was the same with the seat. We had our standard seat, and we wanted a seat that is thinner, that looks better. They were completely confused: “A thinner seat?” They’d never done that—a flatter seat, a more uncomfortable seat. But it looks better.

Roland: “But how can we explain it? How can we name it? It’s not a comfort!” No, it’s style. It’s custom.

Does the custom scene really affect what you do as an OEM?

Ola: Of course. It’s actually quite simple: we’ve been customizing bikes our whole life, so we live and we work in that scene. All our friends are customizers, this is what they do. So you see exactly what they are going through.

When we started talking to our friends, they were like “Yeah, that’s a cool thing, you guys should do that, but we just know that the electric system will be a bitch.” So we said “OK, we need to something different here. We have to make it work for these guys.”

Roland: I made the architecture ready to customize. That means the frame is four parts, and the wiring loom is three different looms. You have one that is needed to run the engine, and then you have the other ones for the lights and the indicators, to make it easy to change.

You wasted no time getting the nineT to customizers too…

Roland: When we started with all these customizers, we had only one rule: no rules. We said: “We won’t give you any direction, you do what you want to, so you can say after that this is a Blitz bike, this is an El Solitario bike… a bike which carries your personality.”

Ola: Some guys got really confused. We said, “You’ve got a bike, you’ve got the money.” “OK, what do you want me to build?” “Whatever you want.” They’re so used to working with customers, they didn’t know what to make of it.

Roland: It was very important to pick the right customizers. So we sat down together, Ola and me, and we looked at it in a global way. Who would fit, who would be the right guy? Guys that have been doing BMWs for years, and also from different countries. Because we wanted to have maximum variety, to make sure at the end of the day we didn’t have five cafe racers, or five scramblers. And it worked out perfect. If you see the bikes, starting with Roland Sands’ Concept 90 till the very last—the Japanese ones—they’re so different.

Ola: And they really nailed the personalities of each guy.