Not sure quite what you’re looking at here? Neither were we when this brute caught our attention in the magazine Performance Bikes. So we dug a little deeper.

Yes, it says ‘Aprilia‘ on the tin, but it’s not really an Aprilia. It just happens to be powered by a heavily reworked 998cc v-twin, taken from a crashed second generation RSV 1000 R.

This is a completely bespoke, hub-center-steered special—built by a guy named Shaun, in a shed in north England. Oh, and just so that we’re clear, Shaun doesn’t build bikes for a living; it’s his hobby.

“I’d never ridden a center hub-steered bike, and no-one would lend me one,” says Shaun, who asked us to withhold his surname for the sake of anonymity. “I’d read quite a bit about them, and wanted to see for myself what it was all about…and I like making stuff.”

“Start to finish the project has taken three years—However, this includes an 18 month break, while I moved house and workshop. All parts, other than engine and some ancillaries, are made in my home workshop—which is just 18 feet square, but full of tooling.”

“Most of my machine tools were bought at auction and restored by me. My CNC mill I converted from manual to CNC about 14 years ago—most of the electronics are home made. Other stuff’s been collected over the past 40-odd years.”

“Some of my methods may seem unusual, but this is usually dictated by my equipment—or lack of. My philosophy is simple: make as many of the parts as I can myself. If I can’t make it, then redesign it or make a tool so I can.”

Shaun’s process includes some CAD design, CNC and manual machining, and various other fabrication methods. So his hands formed everything you’re looking at here—right down to items like the master cylinders and radiators.

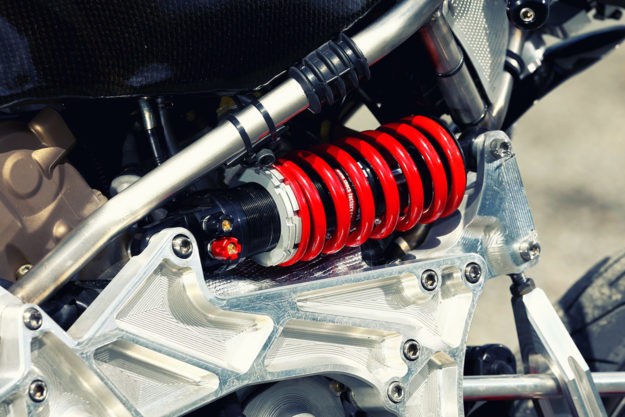

For the steering design, Shaun took cues from the godfather of hub-center steering: the late Jack Difazio. The swingarms are made from oval T45 tubing, and are mated to 7075 billet axle boxes at both ends.

“These axle boxes are easily changed,” explains Shaun, “allowing wheel base and front and back weight distribution to be altered. The steering setup is one of three I intend to try—please bear in mind, this an experimental bike.”

The top tubing part of the chassis is made from Inconel—a corrosion-resistant superalloy. “I had some left over from another job,” says Shaun, “and it allowed me to make modification by welding, because it didn’t need painting.” The main chassis section has been machined from 6082 T6 aluminum.

Among the rare parts that Shaun didn’t make are the shocks. These were custom-built for him by Mike Capon of M Shock. “These are simply superb,” says Shaun.

The wheels are Yamaha R1 units, but the front’s been modified with a hand-made hub. The R1’s Tokico calipers were originally fitted too, but they’ve since been replaced with a Brembo items.

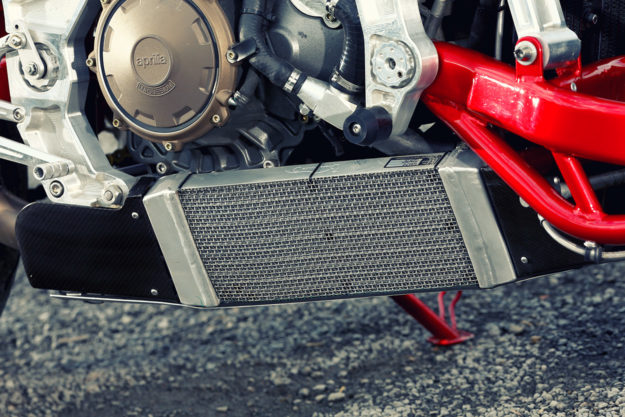

Even the cooling system is a one-off. “This was my biggest worry,” says Shaun, “but it turned out to be OK.” Pace Performance supplied the radiator cores, while Shaun made the end and header tanks, and a new water pump housing.

Naturally, the donor engine’s had some work done too. “I’ve modified the engine quite a bit,” says Shaun. “This includes mods that allow me to run the Gen 1 electrics, which are better for tuning purposes.”

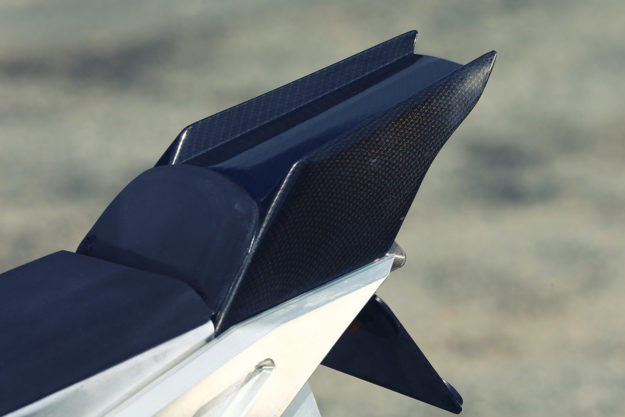

For bodywork, Shaun fabricated an aluminum tank and tail, which were painted satin black and given a carbon fiber finish. We’re usually not fans of faux carbon, so we’re laying down the gauntlet, and challenging Shaun to shape his own carbon parts next time.

Admittedly, that’s a bit cheeky, since Shaun’s even gone to the trouble of designing and building his own controls and master cylinders, and other bits like the rear-sets and yokes. All critical fasteners are titanium, and the rest are a mix of 8.8 or stainless steel.

So after all that, what’s it like to ride? “To be honest, first time out I thought I’d ride it down our back lane, feet down, to sort of get a feel for it,” says Shaun. “However after about ten feet, both feet were on the pegs—I rode to the end of the lane and turned right onto the main road, and rode it round a four mile circuit, doing four laps the first time out.”

“The only thing I can say, is it was unsurprising! Other than it doesn’t dive under braking, it steers quite neutral—but one thing that became apparent was the rear being too hard, so this has since been changed.”

He’s since put another three thousand miles into the bike. “Over this time I’ve made a few adjustments to suspension setup and steering, rake, trail, ride height, etcetera. This was done more to find out how it reacts to changes, rather than to improve things. After doing these changes it was pretty much put back to how it was initially setup!”

“All up weight including fluids is 178 kilos (393 pounds), with the weight distribution 51% to 49%, front to rear. It was tested by Performance Bikeslast summer, and they stated in the magazine, ‘It’s the best special we’ve ever tested.’”

Shaun’s not done though. He’s working on incorporating the clutch and brake fluid reservoirs into the handle bar stubs, and making a new rear suspension rocker to bring the rising rate down. “The other steering systems I have in mind may or may not get done,” he says, “depending on mood and time.”

As for other projects, there’s a Velocette Venom on his bench that’s almost fully restored, but he’s not sure what’s after that. “Possibly my take on a Hossack front end,” he quips, “or another bike like this one, but with an RSV4 engine and some other changes.”

“I’m sort of waiting for inspiration. Any suggestions?”

With kind permission of Performance Bikes magazine | Images by Chippy Wood.