The concept of the patron is well established in the world of art. Charles Saatchi is almost a household name in the UK, but before him we had New Yorker Peggy Guggenheim—who anchored the careers of Pollock and Rothko.

The concept of the patron is well established in the world of art. Charles Saatchi is almost a household name in the UK, but before him we had New Yorker Peggy Guggenheim—who anchored the careers of Pollock and Rothko.

Parallels are now edging into the modern custom motorcycle scene, and one of the leading lights is Bobby Haas of the Haas Moto Museum in Dallas.

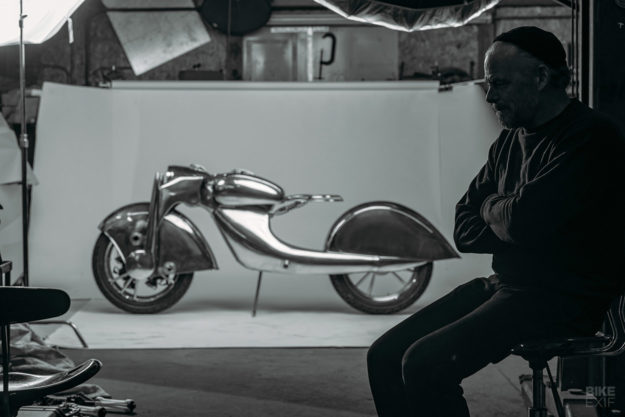

Bobby has built up a collection of 130-plus extraordinary motorcycles, and occasionally commissions them too. Hazan is one of his protégés; Craig Rodsmith is another, and his incredible front wheel drive motorcycle is the latest resident of the hallowed halls.

It’s a classic story of patron and artist working in tandem, and begins when Bobby was suffering from a bout of insomnia while visiting the Handbuilt Show in Austin, Texas last year.

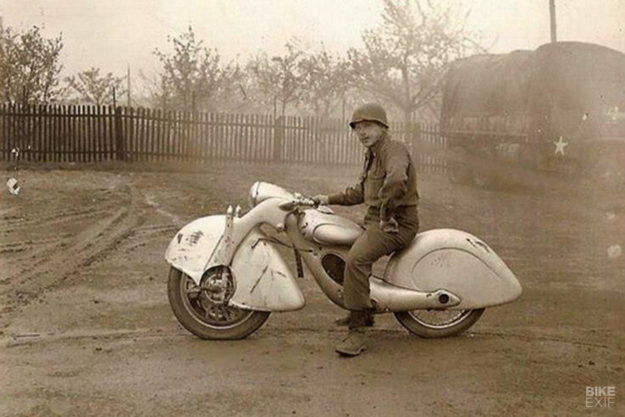

“After a sleepless night, I started surfing the net,” he tells us. “I came across grainy photographs of an Art Deco bike concocted by a group of German engineers in the 1930s.” It was the Killinger und Freund machine built between the wars in Munich.

Bobby immediately thought of Craig Rodsmith—and texted the US-based Australian expat at 3:00am. They met in the lobby of the hotel Bobby was staying in—but Craig wasn’t immediately convinced.

“When I proposed the idea of using this German contraption as the inspiration for a custom build, I could see the doubt in Craig’s eyes,” says Bobby. “Which was why I knew that Craig was the right person to execute this vision.”

Craig admits that he was less than enthusiastic.

“At first, I was intimidated,” he says. “I thought he’d chosen the wrong man for the job. But Bobby believed the bodywork had ‘me’ written all over it, and should be done in polished aluminum.”

It didn’t stop there. The bike was also to be front wheel drive, with a radial engine inside the front wheel. But Craig agreed to the project, thinking he could just buy a radial engine online and adapt it.

“Well, as it happens, they are not exactly readily available,” Craig says. “So I decided I’d make my own. How hard can it be?”

He located three identical 60 cc two-stroke engines. “I whittled them down and made a unified crankcase,” he reveals. “Although they’re really three individual cases combined.”

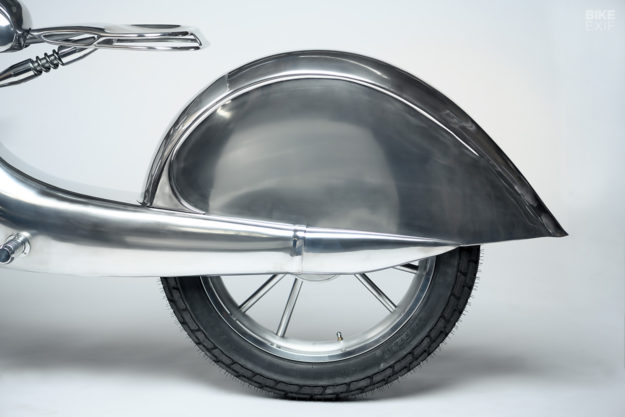

“Then I had to determine the wheel size. With a little coaxing, I managed to get the engine inside a 19″ rim. I needed a pair of blank and undrilled wide aluminum rims, so I turned to Matt Carroll.”

“He’s an encyclopedia of wheel knowledge and got me a set of 3½ by 19 inch rims with a shallow center, to give a little more room.” Incidentally, the front wheel is unique because it can only have spokes on one side—so the fuel lines and control cables can run unimpeded.

Conventional motorcycle engineering obviously does not apply here. After all, the front axle needs to rotate and support the engine, and also drive the front wheel.

“Another problem was how to start it,” says Craig. “So I made an electric start system, which would need to basically start three engines simultaneously—and in a limited space. I then made my own Bendix drive, so the starter would disengage once the engines were running.”

Craig makes it sound relatively easy to put an engine inside a wheel, but then again, we’re not sure that he is entirely mortal.

To send engine power to the wheel, Craig has used a lay shaft, which drives a centrifugal clutch, which drives a final drive sprocket, which drives a shaft with a flange that the wheel is bolted to. Got that? Piece of cake!

After all this mechanical ingenuity, it was time to move to more familiar territory: building a chassis from scratch. “I made an aluminum lattice-style frame with upright fork legs,” says Craig. “So the wheelbase doesn’t change as the forks travel up and down.”

It’s worth noting that Craig did all this without any 3D design or CNC machinery. Instead, he’s gone the traditional route, using a small 70-year-old manual lathe and mill, along with files, hacksaws and hand tools.

His approach to the bodywork was very similar. He hasn’t even used bucks or power tools—just a hammer, dolly and English wheel.

“I wanted the body to flow, almost as if it was liquid,” he says. “I’d like to think I’ve almost got it proportionally right, from the wide front with an integrated headlight to the tapered rear body, giving it a streamlined appearance.”

Craig even made the tiny shock absorber that suspends the aluminum seat. And other exquisite details like the gas cap and ignition switch, and countless little bezels—mostly fastened with tiny stainless 1.5 mm screws to keep visible fasteners to a minimum.

“I think one of my favorite features is the scoop on the front fender,” he says. “Bobby and I discussed using a grille so that the detail of the engine was somewhat visible—in the end we opted for a scoop, which opens like a door and keeps the body appearance smooth.”

The result is one of the most striking builds we’ve seen over the past ten years. And we’re curious to know what it’s like to ride, since there are no contemporary reviews of the 1935 Killinger und Freund that inspired this machine—and its name, ‘The Killer.’

“It’s a running, rideable bike,” says Craig. “But I haven’t ridden it much, for two reasons: I live in the upper Midwest so there’s been too much ice and snow, and it was built primarily as a functional art piece.”

“But it’s a weird sensation of being pulled by an engine rather than pushed.”

Bobby Haas is happy. “I know from personal experience that success is all the sweeter when you accept a challenge to do something you think you’re destined to fail at. My role is to enable genius artisans to create a masterpiece that might otherwise escape reality, and just drift away as a pipe dream.”

Craig has turned this particular pipe dream into reality, and in the process, blurred the distinction between engineering and art. It might not be the ideal steed for an Iron Butt Rally, but it’s a clear indication that the past still influences the future. And old school fabrication skills are still out there, if you know where to look.

See it for yourself on display in the Haas Moto Museum.

Rodsmith Motorcycles | Facebook | Instagram | Haas Moto Museum | Images by Grant Schwingle